If you like this piece, read more about where we stand and sign up to get our occasional email bulletins!

Introduction

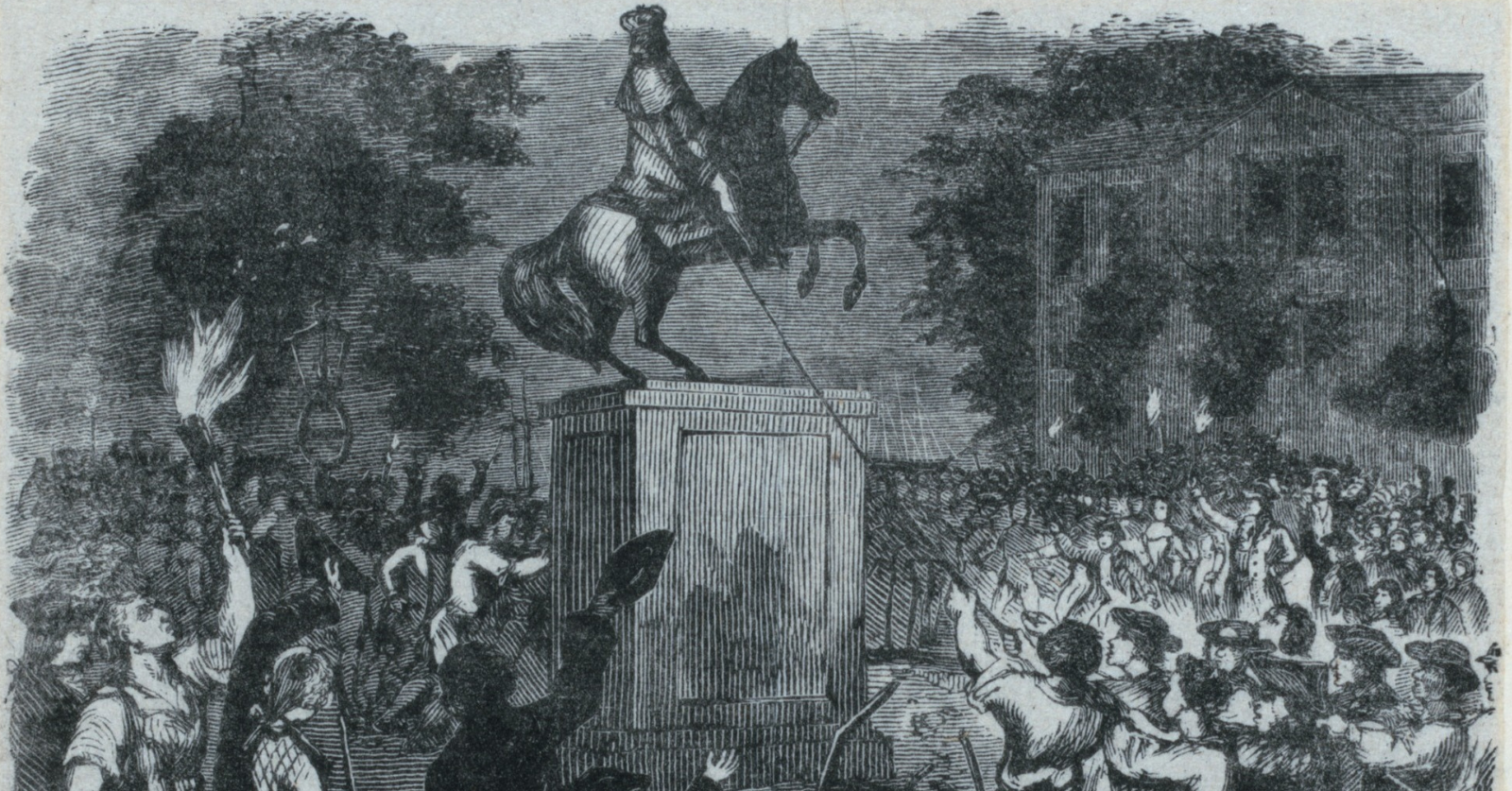

Forty-five years ago today, on September 11, 1973, the Chilean military, backed by the United States and Chilean capitalists, conducted a coup d’etat against democratically elected president Salvador Allende. Allende, a Marxist and anti-imperialist, died in a military assault on the presidential palace. Thousands of his supporters were tortured and murdered, and thousands more were forced to flee the country to avoid the same fate.

The horrors of the coup and the dictatorship that followed often overshadow both how inspiring Allende’s victory and government were for working-class Chileans, as well as the contradictions, pressures, and mistakes that plagued Allende from the very beginning of his time in office. Any socialist elected to executive office today would face many of the same problems, and more.

In publishing his victory speech, we aim both to remember Allende and an inspiring moment in the history of democratic socialism and to learn from a movement that faced serious constraints and contradictions in a concrete historical situation.

Given the long history of relative political freedom and electoral democracy in the United States, the beginning of a transition to socialism in this country will bear important similarities to Chile’s, with its mix of mass workplace organizing and legislative reforms aimed at developing ever greater popular control. For this reason, the Chilean experience offers both inspiration and important warnings for democratic socialists who think strategically about a transition in terms of a “democratic road to socialism.”

Allende was a well known figure in Chile long before the 1970 election. He had run for president in the three previous election cycles. His campaign — based on an explicit platform of class struggle and expropriation of private capital in favor of social ownership and democratic control — inspired thousands with its rhetoric of freedom, democracy, dignity, and economic security. The working class and peasant majority, many of whom were desperately poor, rallied around not only Allende but around the possible future he represented.

Popular Unity — a coalition including Allende’s own Socialist Party as well as the Communist and smaller leftist parties — envisioned Allende’s presidency as a preparatory stage. They would avoid direct conflict with small- and medium-sized capitalists in order to first take hold of the “commanding heights” of the economy. And they would use the wealth generated by newly state-controlled basic industries — primarily copper mining — to begin to enact redistributive policies that would prove popular enough to generate a legislative majority for a more aggressive push towards socialism by 1976.

Upon assuming office, Allende and Popular Unity immediately began carrying out their program. The most significant features were strong protections for worker organizing, improved schools and child nutrition, the beginning of a national health service, a dramatic increase in social housing construction, a policy to never use force against public demonstrations, the beginnings of worker co-management of some workplaces, and the nationalization of basic industry — again, primarily copper, the country’s most significant export. The impact of these policies was huge and immediate. In some firms, workers began to take control of their workplaces, though this process was uneven. Many people, including many children, could see a doctor for the first time in their lives. Real wages rose an average of 30% in a single year.

But right away, there were problems. Pro-capitalist and right-wing parties stalled and hassled Allende in the legislature. Some parties in the Popular Unity coalition, especially the large and well-organized Communist Party, argued the government was moving too quickly; other coalition partners argued it was going too slowly. Capital strikes and increased consumer demand from workers dramatically increased incomes led to shortages. American copper companies dumped cheap product into the world market in order to drive down prices and make an example of Chile by undermining its economy. The United States even led an unofficial but effective trade blockade against the country.

Despite all this, Popular Unity only grew stronger.

But as support for the Left grew, the Right resorted to increasingly obstructionist, violent, and illegal tactics. Perhaps Allende’s greatest failure was his insistence on maintaining strict adherence to legality and procedure, even as his opponents tried to undermine him by illegal means. Arguably, Allende did not even make use of legal channels to prosecute opponents who worked to illegally undermine the elected government. And because he was never entirely comfortable with many of the processes of worker self-organization — the “revolution from below” that his election inspired — the lifelong Marxist ended up in the untenable position of encouraging the working class to slow down and moderate its demands.

Thus, despite the massive material gains and Popular Unity’s increased popularity, the working class (in part because of Allende’s insistence on moderation and the use of the state as the sole arbiter of class conflict) was not strong enough to prevent Chilean capitalists and the U.S.-backed Chilean military from removing the elected government from power. In its place, they installed a brutally repressive capitalist government under General Augusto Pinochet.

As Ralph Miliband puts it in “The Coup in Chile,”

“Allende, as we know, was absolutely set on the course of conciliation – encouraged upon that course by his fear of civil war and defeat; by the divisions in the coalition he led and by the weaknesses in the organization of the Chilean working class; by an exceedingly “moderate” Communist Party; and so on.

“The trouble with that course is that it had all the elements of self-fulfilling catastrophe. Allende believed in conciliation because he feared the result of a confrontation. But because he believed that the Left was bound to be defeated in any such confrontation, he had to pursue with ever-greater desperation his policy of conciliation; but the more he pursued that policy, the greater grew the assurance and boldness of his opponents. Moreover, and crucially, a policy of conciliation of the regime’s opponents held the grave risk of discouraging and demobilizing its supporters.”

While the course Allende took ultimately led to failure, we should also keep in mind that there is no guarantee that a more aggressive strategy would have won, especially given the millions of dollars the United States was secretly paying to Allende’s political opponents and right-wing elements of the Chilean armed forces. Allende saw the course he followed as the only way to avoid open civil war — a conflict he believed his side was bound to lose.

Even with their flaws, Allende and the movement that propelled him to office are a source of deep inspiration for The Call. They show that a democratic road to socialism can gain the mass support of the working class and begin a process of transition, even if Allende’s government ultimately ended in tragedy. The Popular Unity coalition shows that once the latent power of the working class is set into motion and it begins to seriously organize itself as a class, workers are often more radical than their elected officials. We take this, too, as a reason for hope. While there is much to learn, perhaps the biggest and most obvious lesson from the Allende government is that winning elections is a necessary step on the road to socialism, but insufficient on its own. We also need working-class movements that can bolster and defend the program of a socialist government from below while cutting into the power of capital through their own initiative as well. And we need to be prepared to do everything within our power to defend a mandate once it is won against a capitalist class and right-wing forces that have no real respect for democratic legitimacy.

Still, on the anniversary of the coup d’etat, we wish instead to celebrate the high point in both Allende’s life and the socialist movement in Chile in the 1970s, which was also one of the most important moments in the history of democratic socialism. We are proud to publish Salvador Allende’s victory speech, delivered on September 5, 1970. We believe it is published in English for the first time here.

— Ben B., and new translation below by Marianela D’Aprile

Victory Speech (1970)

I am deeply moved as I speak to you from this platform, through these subpar speakers. How significant — more so than words — is the presence of the people of Santiago, who, representing the vast majority of Chileans, congregate here to reaffirm the victory that we won fair and square today, a victory that opens a new road for our country, and whose principal actor is the working class of Chile who are gathered here today. How extraordinarily significant it is that today, I can address the people of Chile and the people of Santiago from the Federation of Students. This is of very high value and significance. No candidate who has won thanks to the will and sacrifice of the people has ever used a platform of greater importance. Because we all know: The youth of this country were the vanguard in this great battle, which was not the battle of a single man, but rather the battle of an entire people; this is Chile’s victory, reached fairly this afternoon.

I ask you to understand that I am only a man, with every shortcoming and weakness that any man has; and if I was able to endure yesterday’s defeat, today, without arrogance and without any spirit of revenge, I accept this victory, which is not personal and which I owe to the united popular parties, to the social forces that have been with us all along. I owe it to the radicals, the socialists, the communists, the social democrats, the members of the MAPU [Popular Unitary Action Movement] and the API [Independent Popular Action], and to thousands of independents. I owe it to the anonymous and selfless countryman; I owe it to the humble woman of our land. I owe this victory to the working class of Chile, which will come with me into La Moneda on the fourth of November.

The victory you reached today has a deep national meaning. I want to make clear right now that I will respect the rights of all Chileans. But I also want to make clear, and I want you all to know for sure, that as soon as we get to La Moneda, with the working class in power, we will fulfill the historic promise that we’ve made: to make reality the political program put forth by Unidad Popular.

I’ve said it before: Our purpose is not, nor could it ever be, petty revenge. Nor could we ever, for any reason, give up on or trade the program put forth by Unidad Popular, which was the banner carried by the first authentically democratic, popular, national, and revolutionary government in the history of Chile.

I’ve it said before, and I will say it again: victory wasn’t easy, and it will be just as difficult to consolidate our victory and build a new society, a new social contract, a new morality, and a new nation.

But I know that you, you who put the working class in power, will have the historic task of turning what Chile longs for into reality: to turn our nation into a country peerless in its progress, in its social justice, in the rights of each man, each woman, each young person of our land.

We’ve triumphed in order to go on to definitively defeat imperialist exploitation, to end with monopolies, to bring about a deep and serious agrarian reform, to control the commerce of imports and exports, to nationalize debt — all pillars that will make possible Chile’s progress, creating the social capital that will drive our development.

That’s why, this evening, which belongs to History, and in this moment of celebration, I express my deeply felt appreciation to every man and woman, to the militants of the popular parties and the members of the social forces that made this victory possible, and who have aims that go beyond the borders of our own nation.

To those in the pampas or in the steppes, to those who are listening from the coast, to those who labor in the foothills of the Andes, to the simple homemaker, to the university professor, to the young student, the small business owner, to every man and woman in Chile, to the youth of our land, to all of them, the promise that I make today, before my conscience and before the working class — the fundamental actor in this victory — is to be authentically loyal in our common and collective task. I’ve said it before: My only wish is for me to be, in your eyes, your comrade who is president.

The anonymous man, the ignored woman of Chile, it is they who have made possible this most important social event. Thousands and thousands of Chileans sowed their pain and their hope in this moment which belongs to the people. From beyond these borders, from other countries, people look onto our victory with deep satisfaction. Chile is opening a path that other peoples across America and the world will be able to follow. The vital power of unity will break the dams of dictatorships and open the course for other peoples to be free and to build their own destiny.

We are sensible enough to understand that each country and each nation has its own problems, its own history, and its own reality. Facing that reality, the political leaders of those countries will be the ones who decide which tactics to adopt. We can only have the best relationships — political, cultural, economic — with each country in the world. We only ask that they respect — there will be no choice but to do so — the right of the people of Chile to have won for themselves the government of Unidad Popular.

We respect and will continue to respect self-determination and non-intervention. But that does not mean that we will shrink in our alliance in solidarity with peoples fighting for their economic independence and for the dignity of human life across every continent.

I only want to carry out before history the significant event that you all have made reality, defeating the arrogance of money, the threat and pressure that come with it; defeating warped information, a campaign of terror, of malice and insidiousness. If a people has been capable of this, it will also be capable of understanding that only by working more, by producing more, will we be able to make Chile progress and give each man and woman of our land their genuine rights: to work, to housing, to health, to education, to rest, to culture, and to recreation.

We will exert all of our creative power to realize the goals laid out by the program of Unidad Popular.

Together, with your efforts, we will bring about the changes that Chile asks for and needs. We will make a revolutionary government.

Revolution does not imply destruction, but rather construction; it doesn’t imply demolition, but rather building; and the people of Chile are ready for this great task in this most significant moment of our lives.

Comrades, friends: How I wish that the media had allowed me to talk more at length with all of you, and that each of you had heard my words, steeped in feeling, but at the same time firm in their conviction to the great task that lies before all of us and that I fully take on. I ask that this unprecedented demonstration come to represent an expression of the conscience of the people.

You will go back to your houses without the least bit of provocation and without allowing yourselves to be provoked. The people know that their problems are not solved by breaking windows or smashing a car. Those who said that in the future, disturbances like these would characterize our victory, will be met with your conscientiousness and your responsibility. You’ll go to work tomorrow or on Monday, happy and singing; singing to this victory so legitimately won, and singing to the future. With the calloused hands of the people and the laughter of children, we will make possible the great task that only a conscientious and disciplined people will be able to carry out.

Latin America and beyond look to our future. I have full faith that we will be strong enough, strong and serene enough, to open up a charmed path toward a different and better life; to start to walk through the hopeful boulevards of socialism that the people of Chile will build with their own hands.

I reiterate my grateful acknowledgement of the militants of Unidad Popular; of the members of the Radical, Communist, Socialist, Social Democratic, MAPU and API parties; and of the thousands of leftist independents who have been with us all along. I express my affection and also my gratitude to the comrades who are leaders of those parties, who — beyond the borders of their own organizations — made possible the strength of the unity claimed by the working class. It’s because the working class claimed this unity that our victory, the victory of the people, was possible.

The fact that we are hopeful and happy does not mean that we are going to neglect our vigilance: this weekend, the people will grab the nation by the waist, and we will dance one big cueca from Arica to Magallanes, from the mountains to the sea, as a symbol of the wholesome joy of our victory.

But at the same time, we will keep our popular action committees vigilant, so that we may be ready to respond to any call — if it were necessary — put out by the leadership of Unidad Popular. They will call on the committees of companies, of factories, of hospitals, of neighborhood associations, on the proletarian population, to consider our problems and their solutions, because we will quickly have to set the country in motion. I have faith, deep faith, in the honesty and in the heroic conduct of each woman and each man who made this victory possible.

We are going to work more. We are going to produce more.

But we will work more for the Chilean family, for the working class and for Chile, with the pride that we have as Chileans and with the belief that we are carrying out a grand and marvelous historic task. In the deepest fibers of my being, in the human depths of my fighting soul, I feel what each of you gives to me. What is germinating today is part of a long journey. I merely take in my hands the torch lit by those who, long before us, fought alongside the working class and for the working class.

We must make this victory a tribute in honor of those who have fallen in social battles and nourished with their blood the fertile seed of the Chilean revolution that we will carry out.

Before I finish, I want to acknowledge — it’s only honest to do it this way — that the government put forth numbers and data accurate to the results of the election. I want to acknowledge that the head of the square, General Camilo Valenzuela, authorized this mass act, with the belief and certainty, assured by me, that the people would congregate responsibly, knowing that they have won the right to be respected in their life and in their victory; the people know that they will come with me into La Moneda on the 4th of November of this year.

I want to highlight that our opponents in Democracia Cristiana have recognized the victory of the people. We will not ask the Right to do the same. We don’t need to. We don’t have any petty feelings against them. But the Right will never be able to recognize the greatness of the people in their fight, born of their pain and of their hope.

I’ve never felt such human warmth as I do now; nor has our national song ever had — for you or for me — as deep a significance as it does now. We’ve said it before; we are the legitimate heirs of the fathers of the nation, and together we will bring about our second independence: the economic independence of Chile.

Citizens of Santiago, workers of this nation: You and only you are the victors. The popular parties and the social forces have taught us this great lesson, which has repercussions far beyond our material borders.

I ask that you go home with the wholesome joy of a fair victory. Tonight, as you hold your children, as you look to rest, think of the difficult tomorrow that lies ahead of us, when we will have to put forth even more passion, even more care, to make Chile ever greater, and to make life in our country ever more just.

Thank you, thank you, comrades. I’ve said it before: My party, the unity of workers, and the unity of the people are the best thing I have.

To your loyalty, I will give back the loyalty of a leader of the people — the loyalty of your comrade who is president.