Credit should be given where credit is due. Bernie is right to call Biden’s stimulus package “the most significant piece of legislation to benefit working families in the modern history of this country” (however low a bar that might be). Through direct payments, the American Rescue Plan boosted incomes for most working-class and middle-class Americans. It created a temporary child tax credit. It extended generous unemployment benefits through September. And it bailed out state and local governments to prevent a return to austerity.

The stimulus package is a significant and ambitious effort to resuscitate a weak economy, and working people would be much worse off without it. And while it’s slightly smaller than the CARES Act signed into law by President Trump in spring 2020, the American Rescue Plan focuses almost all its support on regular people rather than on bailing out corporations.

The move has some liberals wondering whether they finally have a real friend in the White House. Anand Giridharadas speculates that Biden’s presidency may be “transformational.” The Daily Beast alerts progressives: “Meet your new hero: Joe Biden.”

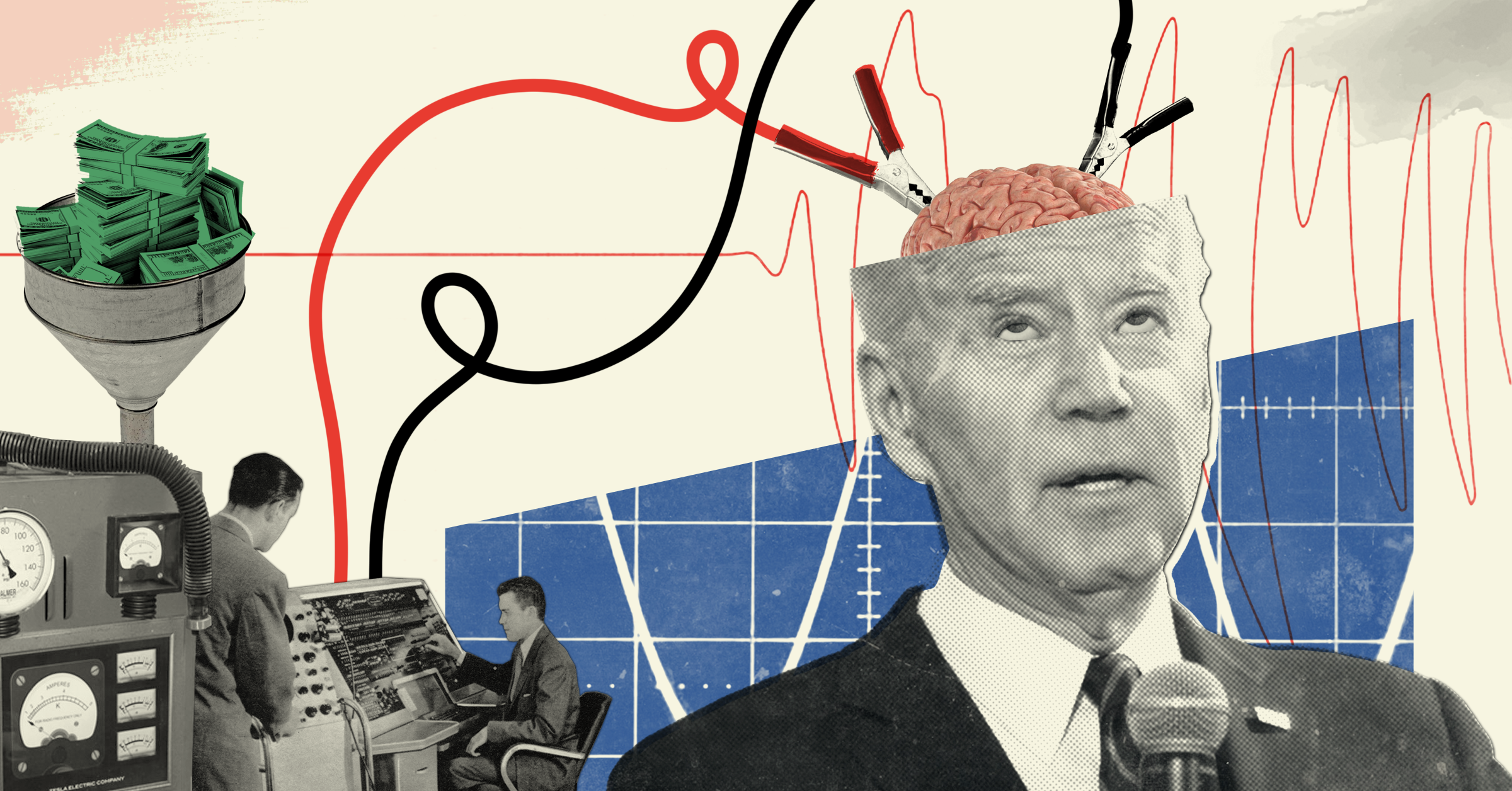

It is true that Biden’s economic policy so far marks a shift from Barack Obama’s austerity regime and Donald Trump’s tax cut orgy. But the question for the Left is not where Biden’s heart is at. It’s this: who holds the power? The answer to that question will determine the opportunities and limits for reform in the next four years.

On closer inspection, there is reason to be dubious of the triumphant cheers from the progressive wing of the Democratic Party. Biden may have broken with the logic of austerity. But that’s no test of whether the corporate world still holds power in D.C. and inside the Democratic Party itself — and whether they’re ready and able to shut down further reforms. In fact, a close reading of developments in the last year shows that Biden’s anti-austerity shift has the enthusiastic support of the billionaire class.

It’s on the question of whether Biden can significantly increase taxes on corporations and the wealthy, and bring about a fundamental shift in labor law, that we’ll truly see whether the corporate stranglehold on mainstream American politics has been fundamentally changed.

So far, there’s no indication that it has been. Business loved Biden’s stimulus (it saved many from economic ruin), but they’ve come down hard on further reforms, and Biden seems to be buckling. And while politicians hem and haw over further spending and redistribution, the real counterpower to corporate control — the labor movement, the Left, and social movements — remains woefully disorganized and ill-prepared for the fights ahead. In such a moment, socialists need to be clear eyed about the challenges, keep emphasizing our differences with the corporate-controlled Democratic Party in order to build a real alternative, and make the case for a new round of struggle against the political establishment.

The Origins of Bidenomics

To fully appreciate where Biden’s anti-austerity shift comes from, we have to go back to 2008.

The Great Recession posed a test to the neoliberal order that it was not prepared to respond to. As David Kotz puts it in his review of the economic situation in the last decade:

“The financial crisis and Great Recession of 2008 marked the end of the period when the neoliberal form of capitalism promoted normal economic expansion… Normally… recoveries [from recessions] are relatively rapid, given the presence of ample available labor and unused productive capacity, typically with GDP growth of 4 per cent or higher. However, the recovery after 2009 stands out, with an annual growth rate of only 2.3 per cent. Despite the decade-long expansion following the financial crisis, the GDP growth rate from the pre-crisis peak in 2007 through the peak in 2019 was only 1.7 per cent. Such data clearly indicate a condition of prolonged stagnation.”

To make matters worse, in the 2010s, a sluggish economic expansion was coupled with anemic growth in labor productivity. Between 2007 and 2019, workers’ productivity grew by only 0.8% annually, compared to 2.1% between 1979 and 2007.

At first, despite this stagnation, nothing much seemed to change in the world of mainstream politics. After passing a relief package that most economists now concede was far too small, Barack Obama and the Democrats joined hands with the GOP to slash federal spending and enact a new round of austerity.

But something did begin to change as the decade wore on. After 30 years of singing from the Reagan hymnal, Democratic economists were among the first in the political establishment to begin to question the logic of austerity.

One of the early doubters was Larry Summers. Summers has been a broker between the Democratic Party and the business world since the Clinton years. It was partially under his tutelage that an entire generation of Democratic economists were raised in the ways of Reagan.

By 2013, Summers had changed his line. Alarmed by low growth rates around the world, Summers warned that the global economy was falling into a period of “secular stagnation.” In 2019, he and his disciple Jason Furman were explicitly drawing connections between the social, ecological, and economic crises and urging politicians to drop any commitment to austerity. “Much more pressing [than the federal debt] are the problems of languishing labor-force participation rates, slow economic growth, persistent poverty, a lack of access to health insurance, and global climate change. Politicians should not let large deficits deter them from addressing these fundamental challenges.”

Summers and Furman alone could not change Democratic Party strategy. Throughout the 2010s, the party as a whole showed no sign of making a clear shift in policy. But the strains in the neoliberal order were about to be exacerbated by events, and much more powerful forces would question certain neoliberal assumptions.

Business Changes Its Tune

The COVID-19 crisis and the specter of economic collapse were just the kind of catalyst needed to shift the political common sense in the world of business.

Despite a weak primary campaign devoid of any clear agenda, by the general election Joe Biden was promising a significant stimulus to address the pandemic and economic crisis. But rather than repelling the corporate world, as it might have in years past, the promise of “Bidenomics” acted as a magnet for CEOs and corporate leaders — and their support strengthened Biden’s hand.

A Yale poll of directors at America’s largest companies found that 77% planned to vote for Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election. CEOs also coupled their support for the Democratic Party with their wallets. Data suggests that CEOs from larger companies giving to Biden outnumbered those giving to Trump 2 to 1. Large donors as a whole accounted for 61% of Biden’s war chest.

Biden’s 2020 donor roll reads like a who’s who of America’s ruling class. There are managers and executives from Blackstone, Bain Capital, Kleiner Perkins, Warburg Pincus, and other major Wall Street firms, as well as Hollywood producers, Netflix CEOs, and tech entrepreneurs. Top donors were made “Biden Victory Partners,” and the runner ups were “Protectors,” “Unifiers,” “Philly Founders,” and members of the “Scranton Circle” and “Delaware League.” The donations enabled Biden to open up a huge lead over Trump in fundraising in the last stretch of the campaign.

We can get a sense of what motivated the majority of leaders from almost every sector of big business to consolidate behind Biden thanks to the scribblings of one of Wall Street’s greatest titans.

Jamie Dimon is the billionaire CEO of JPMorgan Chase. The neoliberal era has been very good to Jamie. But the last decade has weighed on him, and Dimon now questions some parts of the neoliberal common sense that made him rich. Indeed, he sounds very much like he has meditated on the warnings of Summers and Furman and other Democratic economists and come out of the experience with a slightly altered worldview.

In his 2020 shareholder report, Dimon blames long-term stagnation and policy decisions for low growth rates. “All of this broken policy may explain why, over the last 10 years, the U.S. economy has grown cumulatively only about 18%. Some think that this sounds satisfactory, but it must be put into context: In prior sharp downturns (1974, 1982 and 1990), economic growth was 40% over the ensuing 10 years.”

But Dimon doesn’t stop there. He argues that secular stagnation and inequality are at the root of the country’s political crisis as well.

“Americans know that something has gone terribly wrong, and they blame this country’s leadership: the elite, the powerful, the decision makers — in government, in business, and in civic society. This is completely appropriate, for who else should take the blame? And people are right to be angry and feel let down… Our failures fuel the populism on both the political left and right… Many of our citizens are unsettled, and the fault line for all this discord is a fraying American dream — the enormous wealth of our country is accruing to the very few. In other words, the fault line is inequality.”

The challenge now, Dimon argues, is to cut populism on the left and right off before it makes matters worse. (Who knows precisely what Dimon is referring to here, but it seems reasonable to guess that he had Trump and Bernie on his mind.) “[P]opulism is not policy, and we cannot let it drive another round of poor planning and bad leadership that will simply make our country’s situation worse.”

Dimon dreams of a new “Marshall Plan” for the United States. Among other things, he’d have the government raise the minimum wage to boost labor force participation. He’d make the safety net less complicated and easier to access, and introduce childcare programs to help struggling parents. He’d eliminate surprise billing in healthcare and introduce a national catastrophic insurance option (though the details of what that would look like are unclear). He’d spend hundreds of billions of dollars per year on infrastructure. And he’d enact comprehensive immigration reform.

Business Backs Bidenomics

If Dimon’s dream and the consolidation of big business support behind Biden suggest that corporations were ready to abandon austerity in 2020, their actions in 2021 leave no doubt. And it’s to this shift in the corporate world that we should credit Biden’s own progressive turn.

As soon as Biden was elected, the business world quickly closed ranks around the demand for a new and massive stimulus package.

Michelle Gass, CEO of Kohl’s, put the matter bluntly in explaining her support (and the support of other major retailers) for a new stimulus package targeted at regular people: “Anything that puts money into the pockets of our consumers is a good thing.”

A bad monthly jobs report in February was interpreted as a good sign by a major investment manager because of the effect it might have on boosting the size of the stimulus. “[I]t’s one of those cases of ‘bad news is good news,’ at least as far as the markets is concerned, as it increases the chance of a large package.”

Even small business owners, who were relatively more supportive of Trump than their big business counterparts in 2020, enthusiastically backed a major new stimulus. A CNBC survey showed 61% of small business owners supporting the package.

An economist at Deloitte asserted confidently: “What’s good for America is good for banks. The relief bill will keep people from defaulting on mortgages, the money for [the Paycheck Protection Program] will keep businesses that might have outstanding loans from failing, and so on.” The trade paper American Banker concluded: “In this crisis, the White House and banks are on the same team.”

So great was the corporate world’s hopes for a massive stimulus that even the smallest rumors about its fate could send the market into a tailspin or a boom. In late January, when the market feared that Biden might cave to Republican objections to the large price tag for the stimulus, stocks collapsed and Wall Street had its worst day in months.

In early February, Biden convened a meeting of corporate leaders to make the case for the stimulus package. Jamie Dimon, Doug McMillon of Walmart, Tom Donohue from the Chamber of Commerce, and Marvin Ellison from Lowe’s were among the CEOs courted. Business rejoiced in its new found closeness to the White House. (Josh Bolten, CEO of the Business Roundtable gushed about the administration: “The communication with the business community is good and the tone is good.” Mike Sommers of the American Petroleum Institute noted: “My CEOs have been pleasantly surprised at the level of engagement that the industry has received so far.”)

Biden didn’t have to wait long for this ritual courting of big business to pay off in the form of a corporate blessing for the stimulus. In late February, 170 business leaders in New York City — including David Solomon of Goldman Sachs, Stephen Schwarzman of Blackstone, Larry Fink from BlackRock, and Ken Jacobs from Lazard — signed a letter to congressional leaders enthusiastically endorsing the relief plan.

Right after the $1.9 trillion act was finally signed into law, a quarterly poll by the Business Roundtable showed a sharp jump in CEOs’ confidence in the economy and plans to hire and invest. The Business Roundtable’s CEO called it “among the sharpest and quickest recoveries in optimism in the history of our survey.” A similar poll from the National Association of Manufacturers showed member optimism jumping to a high of 88%. A Yale poll of 80 CEOs in the middle of March showed 71% support for the stimulus — about the same as the 70% of the public who supported it. The poll also found retailers and leisure industry executives buoyant about the possibility of direct payments translating into rising profits.

Reviews from prominent business leaders were similarly enthusiastic. Eric Schmidt, Google’s CEO, observed: “So far [Biden] seems to understand where the money needs to go. The typical business person will say things are good at the moment.” James Taiclet, CEO of Lockheed Martin, boasted: “The Biden administration clearly recognizes that we’re all in the era of this resurgent great power competition. I do see strong opportunities going forward under this administration for international defense cooperation, and that would benefit Lockheed Martin, I expect.”

By the end of March, big business’s big bet on Biden seemed to be paying off.

The Coming Fights

The question now is what comes next.

Since enacting the American Rescue Plan, Biden and the Democrats have announced new goals of boosting infrastructure spending and expanding the social safety net.

The infrastructure package (the “American Jobs Plan”) initially included $2 trillion in spending over the next few years, to be paid for by raising corporate taxes. It will put more money into transportation infrastructure and electric vehicles, various ecological initiatives, subsidies for manufacturing and R&D, senior and disability care, and broadband and job training. The expansion of the social safety net (the “American Families Plan”) includes $1.8 trillion in spending on education, childcare, and paid family leave.

Once again, the spending proposals mirror ideas popular in the corporate world. After the American Rescue Plan was passed, the Business Roundtable began an enthusiastic push for infrastructure spending on transportation, broadband expansion, and various green initiatives. The childcare proposals in the American Families Plan mirror Dimon’s own vision for a new Marshall Plan for the country.

But unlike the relief bill which was paid for by borrowing money, these new initiatives initially were to be paid for by higher taxes. And the proposals to raise the corporate tax rate to 28% from 21% and to increase various taxes on the wealthy have been the subject of special ire from the ruling class.

Right out of the gate, the Chamber of Commerce denounced the proposed corporate tax increases as “dangerously misguided” — even though the plan would not even restore the rates to their pre-Trump level of 35%. The CEO of Raytheon warned of a 20% cut in the company’s investments if the hike went through. After learning about the administration’s plans to double the tax rate on the wealthiest, various investors described the plan as “insanity,” a threat to “the golden goose that is America,” and a “slap in the face of entrepreneurs.”

The administration immediately began to cave. Right after announcing the plans, Biden officials responded to corporate pushback by insisting that they were open to scaling back their ambitions. Pete Buttigieg, Biden’s Transportation Secretary, assured ABC: “I think we’re going to find a really good, strong deal space on this. We know that this is entering a legislative process where we’re going to be hearing from both sides of the aisle, and I think you’ll find the president’s got a very open mind.” Brian Deese from Biden’s National Economic Council told Fox News Sunday: “If people think this is too aggressive, then we’d like to hear what their plans are. It’s something we want to have a conversation about.” (By people Deese presumably meant leaders from the corporate world.) Speaking to more than 50 CEOs from Google, AT&T, Dell, Ford, Intel, and other companies, Biden’s Secretary of Commerce said of negotiations with the corporate world: “I’ve been encouraged. Nobody likes to talk about the pay-fors, but there is room for compromise.”

It seems now that Biden and his team are close to reaching that “deal space.” The White House seems to have dropped the push for a corporate tax increase at all in the latest bill, and scaled back the package size to $1 trillion.

And if the rest of the track record of the administration so far is any indication of what’s to come, the chances that the Biden team will pick a big fight with their corporate backers seem slim. When the Senate parliamentarian raised technical objections to including a plan to raise the minimum wage to $15 in the stimulus package, the administration seemed more relieved than anything else. The White House has been similarly noncommittal in response to labor demands to use parliamentary tricks to pass the PRO Act (a major set of labor law reforms). On any question of actually shifting some power to working-class people, the administration’s commitment to reforms suddenly seems to evaporate.

Can We Push Back?

There should be no doubt that in the fight to define what the Biden administration is about, the corporate world is active on all fronts. As with administrations past, corporate leaders are exerting enormous influence to define the limits of what’s possible. And for the time being at least, they hold the power. There may be some room for more spending and less austerity thanks to changing business interests and the fear of a return to secular stagnation. But if business gets its way no major move that significantly encroaches on its own power — either in the form of corporate tax increases or a strengthened labor movement — will be tolerated.

Not that business always gets its way. Though American politics have always been defined first and foremost by the rules set by the dominant businesses in a given era, some periods have seen greater concessions thrown to the working class than others.

It takes powerful social movements and left-wing projects — coupled with administrations that are at least willing to compromise, for whatever the reason — to win these kinds of reforms. If there’s hope that Biden’s administration may yet be a means for winning some big changes that could strengthen the working class, it’s to be found here.

And in some ways, the often-made comparison between Biden and Franklin Roosevelt is a useful one for understanding what it’ll take to actually challenge corporate power and win.

Like Biden, FDR started his administration by breaking with some elements of economic orthodoxy. But on the whole, FDR’s first few years (1933-1934) were concerned with restoring the profits of major corporations. In turn, FDR enjoyed support from business early on.

It was only in 1935 that FDR’s administration began to really entertain more ambitious reforms. Labor law reform, national labor standards, and Social Security were put on the agenda — against the wishes of many of FDR’s former friends in business.

But it was not out of the goodness of the Democrats’ hearts that this shift was engineered. FDR, after all, initially opposed significant labor law reform. It was only, as Michael Goldfield describes, under pressure from major social unrest that the administration changed its tune.

In 1933, more than 1 million workers went on strike, a threefold increase from 1932. And that was followed by almost 1.5 million workers in 1934. Nearly simultaneous major strikes in Toledo, Minneapolis, and San Francisco in that same year revealed a rising militancy in the American working class.

Unemployed movements rocked many of the country’s urban centers, and the Communist and Socialist Parties played leading roles in these actions. A funeral for four murdered Communist activists in Detroit in 1932 drew somewhere between 20 and 40,000 attendees. The Scottsboro case threatened to precipitate a mass movement among Black workers.

As labor struggles heated up, the labor movement applied direct pressure to win labor law reform. The AFL held mass rallies to build support. A rally at Madison Square Garden drew 25,000 working-class people — and just as many assembled outside. The following day, a quarter of a million garment workers went on a one-day strike to support reform.

Labor law supporters seized on the protests to strengthen their hand in Congress. Senator Robert LaFollette Jr. warned that absent reform, the movement was an “impending industrial crisis,” one that would “bring about open industrial warfare in the United States.”

But today, for now at least, no such energy at the base exists.

The Black Lives Matter rebellion in the summer of 2020 was the closest we’ve come to something similar, but the mass protests have subsided.

Climate activists bemoan the lack of militancy in the climate movement to push Biden further.

The labor movement is making some progress in the nonprofit, media, and higher education sectors, but the overall unionization rate continues to languish. Strikes are up in the last few years — but besides the teachers strikes this has not been enough to register as a major national event.

The PRO Act campaign being waged by DSA and the fight for Medicare for All are commendable struggles and deserve support. PRO Act campaigners have successfully shifted the positions of two U.S. Senators. The entrance of socialist legislators into government also strengthens our hand.

But if history is any guide, winning reforms on the scale needed will also require widespread social unrest. And we’re nowhere near, for example, being able to precipitate a one-day strike by hundreds of thousands of workers in a major U.S. city.

The Road Ahead

The low-level of militancy from below is partly the result of decades of anti-Left persecution and de-unionization that have severed the link between socialist politics and the working class. That link was the key to making the rebellions of the 1930s possible. Rebuilding it will take years of hard work. Projects like the rank-and-file strategy and class-struggle elections that put socialist activists back into the working class are essential first steps.

In the meantime, Biden’s administration does mark a shift away from austerity, at least for as long as that shift is profitable for big business. But this is not because Biden and the Democratic Party have been convinced of the need to empower workers and challenge corporate power. Every indication we have suggests that the partial turn in policy is an outgrowth of shifting corporate interests and strategies, a response to low growth and a general fear of populism.

Don’t take my word for it. Many remember Biden’s promise to donors in the summer of 2019 that “nothing fundamental would change” if he won, but few know the full context. This is Biden on what his administration would do:

“The truth of the matter is, you all, you all know, you all know in your gut what has to be done. We can disagree in the margins but the truth of the matter is it’s all within our wheelhouse and nobody has to be punished. No one’s standard of living will change, nothing would fundamentally change. Because when we have income inequality as large as we have in the United States today, it brews and ferments political discord and basic revolution. Not a joke… It allows demagogues to step in and say the reason we are where we are is because of the other. You’re not the other. I need you very badly. I hope if I win this nomination, I won’t let you down.”

In backing Biden in 2020, the neoliberal business coalition that has governed this country since the 1980s showed that it has rethought parts of its dogma, and loosened the leash on policymakers (though it’s far too early to declare the end of neoliberalism). But the real fight for major social reforms — let alone socialism — has yet to begin.

We’re entering that struggle with a powerful billionaire class pressing the administration on all fronts on the one hand, and on the other a working class and left-wing that are not yet able to act as a serious counterweight. Progressives, therefore, who eagerly await the next big moves from the White House are likely to be disappointed. As it has been in the past, hopes for big changes will rise or fall instead with the capacities of the working class to win them from below.