In 2004, PSOL (the Socialism and Liberty Party) emerged as a big-tent, anticapitalist alternative to the PT (Lula’s Workers’ Party), which had implemented cutbacks to the pensions of hundreds of thousands of Brazilian public sector workers. Today, PSOL is a nationally-recognized party with around 300,000 members, 13 federal deputies, 22 state deputies, 80 city councilors, and strong ties to a wide array of social movements.

For democratic socialists in the US looking to build an independent political party, PSOL is an important reference. PSOL shares many similarities with DSA, from facing the challenge of fighting the far-right while maintaining political independence, to having a multi-tendency organizational ecosystem. The contradictions we see in the DSA are well-reflected in PSOL, where they take on a more advanced form given PSOL’s additional experience and greater numbers.

A hotly-debated issue in both organizations has been the role of full-time political leadership. DSA and other movement organizations with staff have already confronted the challenges of bureaucratization, burnout, and the demandingness of activism more generally. In light of these risks, it is important to develop a political framework for full-time political leadership –– especially against the “commonsense” handed down to us by NGOs.

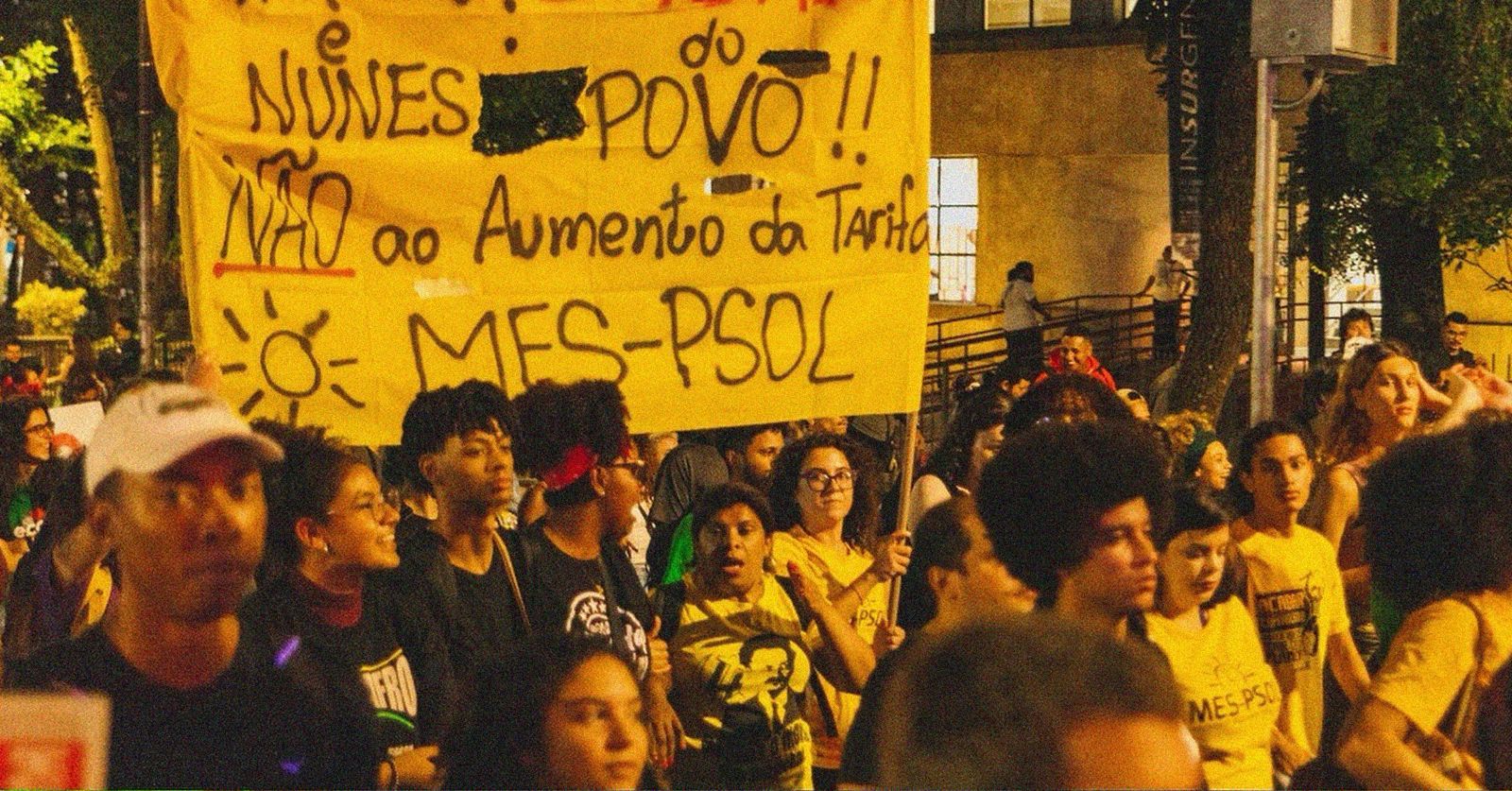

For this interview, Cyn Huang talked with Pedro from PSOL to get his perspectives on the role of full-time political leaders in our movement. Pedro is the chief of staff for Sâmia Bomfim (Brazil’s most popular anticapitalist congressperson), a long-time member of PSOL, and a leader in the Socialist Left Movement (MES), a Marxist tendency within the party.

Cyn Huang: Hey Pedro. Can you start by introducing yourself?

Pedro: My name is Pedro. I am part of the national executive of the Socialist Left Movement (MES) and have been an activist in PSOL (Socialism and Liberty Party) for 16 years.

Cyn: Tell us about the work you do as Sâmia Bomfim’s chief of staff.

Pedro: Well, I can first give a more technical overview and then a political one.

From a technical standpoint, Sâmia is a federal deputy elected from the state of São Paulo. All federal deputies in Brazil have an office in the capital, Brasília, where the parliament is located, and another office in their home state. They are also entitled to have a staff of around 18 to 20 people, a professional, salaried team that serves as the deputy’s advisors.

Her responsibilities include addressing national parliamentary issues while also representing the interests of the people who elected her in São Paulo. In Brazil, candidates are elected statewide rather than by district, so they receive a large number of votes. Sâmia was elected with approximately 250,000 votes — slightly fewer in the most recent election and slightly more in the previous one.

For MES, the most important thing is understanding the political significance of these positions and this structure. We have a principle that a parliamentary representative must first and foremost be a militant [dedicated activist] of the party and the movement. We often say that they are not simply parliamentarians — they are militants who are currently holding parliamentary positions.

Holding office is just one of the many roles a comrade might take on, just like being a union leader or a youth organizer. While parliamentary positions are extremely important — since they serve as key spokespersons and hold significant power and influence within our organization — their role remains one of political activism. Sâmia herself embodies this: she participates in MES’s leadership meetings, engages with PSOL’s leadership, joins grassroots activities, distributes pamphlets, and takes part in a range of political initiatives. She remains on the same level as the working class.

She also continues to claim her original job title — although she is not currently working in that role — as a public servant at the University of São Paulo.

Cyn: What does Sâmia’s team look like? What are all the different roles? How does each member of the team help Sâmia use her platform to organize workers?

Pedro: My role, as well as the role of what we call Sâmia’s advisory team, is to be an organizer. Of course, running an effective parliamentary office requires technical expertise. We have highly skilled lawyers, communicators, legislative advisors, and journalists. While a small portion of the staff are not directly linked to MES, the vast majority are dedicated activists from our organizations.

This orientation leads to an interesting situation — when I travel abroad, people ask me, “Are you part of Sâmia’s office?” And when they ask, “What do you do there?” sometimes I don’t even know how to answer, because it’s essentially a political position where my job is to do whatever is necessary. My official responsibilities include organizing Sâmia’s schedule in São Paulo and contributing to the messaging of her social media platforms. But beyond that, my job as a militant within the office is to strategize:

- What political campaigns can engage the largest number of people?

- What is the mood of the working class at this moment?

- What proposals can attract workers to our ideas?

- What strategies can we use to develop intelligence and data for the office, allowing us to stay in contact with people and mobilize them when needed?

- Which social or labor movements are currently the most dynamic?

- What struggles are happening that we can support through the office, both to help these movements and to introduce them to MES?

For example, if there is a strike at a university where MES has no existing presence, we can approach the movement respectfully and say, “Hello, we’re from Deputy Sâmia’s office.” Most of the time, people respond, “Oh, really? Sâmia is great — can she help us?” We offer support, and through that, we build trust, which creates opportunities to invite them to join PSOL or MES later.

Our policy is that most militants working in parliamentary offices must remain activists first and foremost. This principle must translate into daily practice. For instance, although I work in the office, I am required to participate in and attend monthly meetings of an MES local branch. The branch is the fundamental space where all militants gather to debate and organize.

Most of our activists within the office also work with movements outside of parliament, such as Juntas (a feminist collective), Juntos (a youth movement), or Emancipa (an education initiative). This is how we structure our parliamentary work. I don’t know if this is true for all of PSOL — perhaps some tendencies operate in a similar way, while others may not. Unfortunately, part of the party views parliamentary work in a more traditional way — treating parliamentarians as individual leaders detached from the party base. MES does not allow this to happen.

Cyn Huang: Can you give some examples of what this approach looks like in practice?

Pedro: Two key examples of political action taken by Sâmia’s office illustrate our approach.

1. The Fight Against Bolsonaro’s Pension Reform

During her first term, Bolsonaro’s government passed a pension reform that harmed workers. Sâmia was PSOL’s representative on the parliamentary commission that debated this reform, and she became its main opponent. She delivered powerful speeches, maintained a consistent stance, and became a leading figure in the fight against pension cuts.

At the same time, while she was in Brasília, we launched an online campaign in São Paulo called “Household Committees Against Pension Reform.” This allowed ordinary citizens and workers — whether they were PSOL members or not — to register online and declare their homes as organizing hubs for the fight against the [pension] reform.

Thousands of households signed up, and we established ongoing communication with them. We invited them to join PSOL, sent them printed materials to distribute in their neighborhoods, workplaces, and families, and helped them organize resistance efforts. This was a powerful example of combining legislative action with grassroots activism. Although we were unable to stop the reform, we built a strong movement in the process.

2. Defending the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) Against the Far-Right

In 2023, during Sâmia’s second term, Bolsonaro-aligned politicians launched a parliamentary inquiry commission (CPI) to criminalize the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST). The commission was led by far-right figures, including Ricardo Salles, Bolsonaro’s former minister of the environment.

MST has historically been more aligned with PT [Lula’s Workers’ Party] than with PSOL. While they have a friendly relationship with PSOL, they have traditionally maintained a greater independence from party politics. Although they have softened certain aspects of their program and struggle, they still maintain a respected political tradition in the fight for agrarian reform.

Sâmia emerged as the strongest parliamentary defender of MST, proving that a radical socialist stance is the most effective way to fight the far right. Some moderate and reformist sectors believe that, because the far right is dangerous, the best approach is to be cautious and moderate to avoid risks. However, in reality, the stronger and more decisive we are, the more power we have to defeat the far right.

In response to the CPI, Sâmia and other PSOL and PT deputies faced threats of having their offices revoked. The far right attempted to strip them of their positions. At that moment, we saw an opportunity to go beyond parliamentary action and mobilize in the streets.

We organized a major political event in São Paulo, held at one of MST’s community centers. More than 1,000 people attended. It was not a street demonstration but a large public assembly with speeches, artists, journalists, and even a famous progressive priest, Júlio Lancellotti, who is known for defending the homeless and supporting socialist and leftist movements.

I would say that in 2023, apart from major street protests, this was the largest political event held in São Paulo for a specific cause. It was not only in defense of MST but also in defense of Sâmia and the broader rights of social movements.

Cyn Huang: Can you elaborate on MES’s expectations for professional revolutionaries, or as DSA activists would call them, “full-time political leaders”?

Pedro: Some argue that socialist organizations should not develop a layer of paid, full-time activists because of the risk of bureaucratization. This is a legitimate concern, but we believe that professional activism is necessary for building strong organizations.

Being a “professional activist” does not necessarily mean being paid. It means prioritizing activism in one’s life and striving for the highest level of dedication and competence. Some activists may receive financial support, but their work must always be politically justified. If someone joins a parliamentary office, it should be because we politically determined that it is their most strategic role — not as a career move.

Ultimately, the key is ensuring that political strategy always leads and that activists remain rooted in grassroots movements, rather than becoming detached from the struggle.

It is a political task — it is ultimately a mission. We believe that this is how things need to be organized. There are many risks involved. Because when there isn’t strong strategic clarity, what may seem like an opportunity can also become a risk.

Another challenge is that when a militant starts receiving a salary, they often become more bureaucratized. They might start hesitating — thinking twice about whether to attend a protest, questioning whether it is truly their responsibility. They may think, “Well, that’s not exactly my job, so I don’t have to go.” But the work of a militant is always to do everything possible, to intervene in every opportunity available.

We must be prepared to fight against this tendency toward bureaucratization. However, I don’t believe that this risk should stop us from taking advantage of opportunities to build more and more capacity. To build a strong balance of power and accumulate robust forces within our organizations, it is valuable and important to have comrades who can dedicate themselves fully to political activism.

I, for example, currently dedicate myself entirely to political activism. Inevitably, this gives me more time to focus on strategy — to think about PSOL, to analyze our international relations, and so on.