In the early 1960s, students in Québec’s three major French-speaking universities formed Québec’s student federation, the L’Union générale des étudiants du Québec (UGEQ). The UGEQ fought for free education in 1966 and went on to participate in the 1968 student strikes — strikes prompted by an administrative decision to turn away thousands of prospective students. The strikes lasted a couple of months and ended with the founding of the Universite du Québec, which, similarly to the University of California system, houses several public higher education institutions.

In 1989, one of the more moderate student federations, Fédération étudiante universitaire du Québec (FEUQ) formed, and in 2001 the Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante (ASSÉ), considered the more radical union, was founded. These student associations each have their own general assemblies and strike votes and bring together associations and departments from various campuses.

The 2005 student strike against the transformation of scholarships into loans, and the way the different student unions handled negotiations, highlighted the political differences among these organizations. During negotiations, the more moderate student unions agreed to concessions and accepted the exclusion of ASSÉ from the bargaining table. Two years later, a tuition hike was proposed, and organizers in ASSÉ tried mobilizing a strike for free tuition, but they couldn’t get a member mandate for an open-ended strike.

In 2012, the Québec government proposed a 75 percent increase in tuition over five years. This announcement spurred a series of student protests, which included tactics like occupying the finance minister’s office, ultimately to no avail. That summer, organizers in ASSÉ propagandized and held conferences throughout Québec, situating the hike within the broader neoliberal context. The following fall, 30,000 people protested in the streets of Montreal.

But again, it wasn’t enough to change the government’s plans. ASSÉ then created a coalition with non-member student associations, Coalition large de l’ASSÉ (CLASSÉ), to coordinate a strike effort. They started organizing for strike votes outside of the metropole of Montreal, in the colleges they thought were more likely to approve a strike mandate. Organizers and activists from all over Québec spent the weeks and days leading up to the vote flyering campuses and conducting one-on-one conversations.

The first strike vote won by 12 votes, and just as the organizers had planned, it snowballed from there going campus to campus. With each winning vote, students from more organized associations would recruit and train new organizers on other campuses, moving from one university to the next. A week later, three campuses, with about 20,000 students in total, voted to go on strike. A day later, two of the most important universities in Québec decided on an open-ended strike. The idea of a “Québecois Spring” appeared in the media. By a few days later, there were about 132,000 students who had voted to strike.

On March 22, 2012, three quarters of the province was on strike, with 300,000 people in the streets of Montreal. In late May, 400,000 people filled the streets, in the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history. Around this time a repressive bill was passed, limiting where and how people could assemble and protest, and non-students became involved.

The Maple Spring ended in September when an election was called, the government changed, and the new government did not raise tuition by the proposed 75 percent. (Tuition was, however, adjusted to inflation, and thus increased to a smaller degree.)

This victory was possible only because of the presence of skilled anti-capitalist organizers, an organization with training camps and workshops that had built its credibility over the years by relentlessly fighting for free education, and Québec’s decades-long struggle for higher education as a public good, led by student activists.

We sat down with Morganne Blais-McPherson, a veteran of the Québec student movement, to talk about what the movement was like.

PL: What importance does learning from the Québec student movement have for young socialists today?

MBM: Since I moved to the United States, multiple people have asked me to speak on the Québec student movement and frankly, I haven’t entirely felt comfortable doing so. I was so new when I joined the movement. It was the moment I grew up as an adult. It was the moment I became a socialist, when I became politically active. So I wasn’t in the core of the movement, I didn’t see the decisions being made, my university largely did not go on strike. I didn’t really think I had the kind of experience that one would want to hear about.

But then as years have passed, and I’ve been in different positions in YDSA — I started a chapter at UC Davis, I was on the National Coordinating Committee — as well as holding a role in my union, etc., I realized that even though I wasn’t a lead organizer at the time, I have something to say to young socialists who are thinking about how change happens.

You can’t understand change by looking at tweets or pictures. You need to look at a much longer period of time, considering the multiple decisions that have been made, the mistakes, the wins and losses, the organizations that have formed and fallen apart, to really grasp how something like the Québec student movement won in 2012.

Not many people, especially in the U.S., have been a part of a mass movement that wins — a mass movement that actually is capable of creating concrete change. Being part of that gives a certain perspective on the necessary dynamism of a movement. Multiple tactics are going to be used, and you can’t control that; multiple reasons will drive people to become involved, none of which you can control. And that’s okay.

When I joined the movement, I was completely uninitiated. Two months prior I thought capitalism was a bad word used by brainwashed fanatics. But I showed up every night, I talked about it with friends, and to this day, I have continued the fight for stronger public higher education.

I wish every single DSA and YDSA member could experience the kind of hope that is born from an actual experience of winning through long-term collective action — the fundamental realization that you can’t win big by sucking up to power, but that only unity and courage can get you where you want to be. I have been thinking increasingly this year about how to create the organizational conditions within DSA and YDSA that would best allow members to have such an experience.

Most of us learn as a kid that the world is as it is today. And nothing is ever going to change that. All you can do is work hard, suck up, or get on your hands and knees to beg for scraps. But an experience like the Québec student movement that spans months, where you and others have to work together, work through your fears, and keep at it, changes you. The hope that emerges from that is very strong, and it is the reason I’m still kicking after so many defeats over the years.

The Québec student movement gave me a tempered hope of winning and a tempered approach to loss. I understand that when a moment isn’t seized and a mass movement doesn’t translate into concrete wins, it’s not because the people around me don’t have good intentions. It’s not because they didn’t give it their all, but rather it’s just not our moment. We don’t have the power right now to win. And that means that when we win, it’s not only me, you, and my group of comrades who win. It’s years of comrades that are winning, if not decades. And when we lose, it’s not all about us. Many decisions were made before us.

I have seen multiple campaigns lose. I don’t know how many times we lost rent control [in Sacramento]. I remember giving my all for Prop 15 to raise taxes on the rich in California, but coming up short. Other people gave it their all against Prop 22, the pro-Uber, anti-driver ballot measure in California. At the UC, there was COLA. There was Bernie. Twice. And they were all quite sad because not only did we not win campaigns that would’ve significantly changed the material conditions of the working class, a lot of young socialists became disengaged. And when I say young, I don’t mean only in terms of age. I mean also how long they were politically active in some kind of anti-capitalist or anti-oppression action.

The Québec student movement taught me that you’re going to lose sometimes and then you’re going to win. It’s about the long haul. It’s about using every opportunity you can, every campaign to train people in skills, leadership, building relationships with other organizations, and creating a culture where you have people who support each other, who see each other in good faith, who can disagree and still treat each other in a humane way.

I truly do think that one day, all of these intentional actions and comradely approaches will allow for something like the Québec student movement in the U.S. In 2007, five years before the student movement, the Québec government said that there would be a 75 percent increase [in tuition]. Organizations had tried to call a general strike and they lost. They couldn’t get the strike mandate and a huge hike went through. That was a huge loss for the student movement, but then five years later, they won because they internalized those lessons in defeat.

PL: Could you talk about what the training and culture-building someone gets from being a part of a genuine mass movement were like? What lessons did you learn?

MBM: There are two big lessons that I learned as someone who began as, not hostile to the movement, but disengaged. I’m sure that people who were at the core had very different lessons they took from it, but two things stuck with me the most; The first has to do with collective action and the second with solidarity — what it is and what it’s not.

Collective action: Perhaps my reader feels as I did — small, frustrated, unlistened to, just a faded strip of wallpaper to history, decisions, and debates. But when you, even in your feelings of smallness and inadequacy, decide to join people you’ve never met in your entire life and stay at it for the long haul, you see how numbers really matter. And over time, as you experience collective action work again and again, your presence, even in its numerical smallness, starts to matter. You start to matter to yourself. To paraphrase Lorenzo Orsetti, an Italian comrade killed in action in Syria, you might just be a speck of water, but every storm begins with a raindrop.

My first lesson in collective action was during my first big protest, where I learned that you cannot under any circumstance let a gap open in a march. You need to move as a unit, or else you are opening yourself and others up to risks. Gaps do form, though, and I remember being afraid to be one of those bodies closing the gap. But then I saw a couple of regular-looking Joes do it, and I tentatively went to do so too. Others then joined, and eventually, the gap disappeared, and we were all safe.

A lot of people tell me that they became a socialist by reading, which is unfathomable to me. The truth is that I don’t remember at all the moment when I joined the student movement, because it was like a spirit was controlling my body. I came home from university one day and my body went into the kitchen. The arms and hands of my body took a wooden spoon and lid, and the legs of my body walked to the corner of my street where my neighbors were banging on pots and pans. And then, somehow, I too started banging a lid. The only things I remember were the smiles of the people around me, and the slow embodied realization that I was truly, for once, happy. That’s the power of a mass movement: you get people to join in the struggle for no conscious reason.

Solidarity is a related lesson, and it’s a finicky creature. I’ve made a lot of mistakes in terms of solidarity in my life, but the Québec student movement, because it was so formative to me, becomes a backdrop upon which I evaluate all the mistakes I’ve made.

I learned that solidarity is about taking risks. Solidarity is about acting with the understanding that if I let you go at it alone and fail tomorrow, I might be next. We only get out of it if we are all there for each other. If I leave you alone to your medical bills, your legal bills, if I leave you lying on the street for a cop to then beat you up or arrest you, then tomorrow we’re one comrade down.

And if that repeats itself, you have a dwindling number of people out there, not just because people are out of action, but because then others are too afraid to join in. If I don’t take a risk today — to my physical integrity, to my career, to my social circles, to my bank account at the end of the month — we’re all screwed tomorrow. Sometimes, solidarity truly feels like: if I don’t face my fear and take a hit so that another can stand back up again, we might not get out of here alive. When you’re up against Goliath and his lawyers, journalists, weapons, and lies, solidarity is the only way to sustain a struggle. Over time, that struggle morphs into a mass movement.

PL: Ten years removed, the Québec student movement has been litigated and re-litigated like any movement. Are there any parts of it that you think deserve further analysis? Or that you want to highlight personally because you don’t think it is talked about enough?

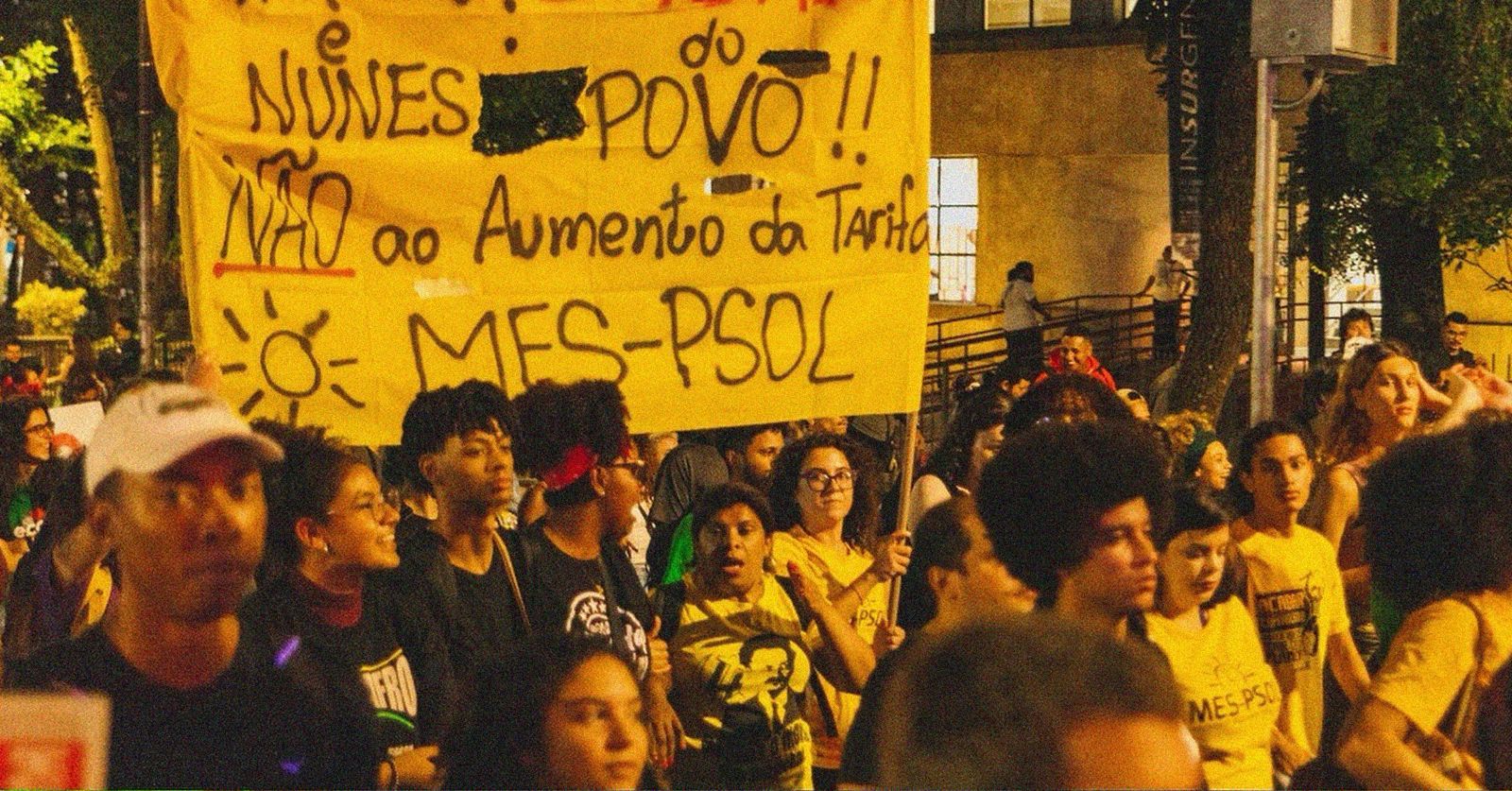

MBM: There was a really strong feminist presence in the movement that’s rarely discussed. Before the student movement I had never met a feminist who was overtly proud of being one. I thought of feminism as a kind of loser fad leftover from the ‘60s. For someone like me, who was not entirely a blank slate but was still new to being in this political environment, being made to think about what it means to be a woman today was super-formative. And that was thanks to the discussions and slogans about the intersections of gender and austerity and capitalism that were going on at the time. People underestimate the importance of banners, signs, and more generally the beautiful artwork that allow people who are new to the movement to approach a theme in a different way.

But it wasn’t all symbolic. I can’t overstate the importance of being surrounded by brave women marching on the front line. It was my first time seeing women collectively being protagonists of their own lives, and this feminist experience has certainly informed my organizing approach. It also served as the spark for my ongoing process of emancipation as a woman.

PL: There’s a difference between a mass response to harsh material conditions and an organized movement that can sustain through the ebb and flow of moments in history. How can socialists try to bridge these conditions and the response with an actual organized political movement?

MBM: Sometimes people approach organizing like management, where we have to limit the types of people, the types of politics, the types of tactics, the types of critiques that we have within the movement. I think that by definition, you can’t do that. A movement exceeds anything an organizer can set out to do, and the student movement was certainly exemplary of that. It’s not like every tactic, every politic that people had within the movement was the same as those of the core group of organizers within ASSÉ. And that’s part of what makes it a mass movement. That’s what makes it dynamic, creative, and innovative. That’s what allows a movement to win.

How do you do that? Intentional leadership development, workshops to grow skills, running campaigns, publications and political education, and most importantly time. The Québec student movement, if anything, shows the importance of time — the time to fail, the time to regroup and think, train, experiment. The time to try again.

And lastly transparent, democratic systems. When members see an organization and its decision-making systems as legitimate, people show up and participate in debate. ASSÉ is a big lesson in that. Debate is that secret ingredient that accelerates the political development you get from concrete organizing experiences.

Debate also allows us to try to understand how different struggles are united in class struggle. Being a socialist organizer, though, is actually taking the time to do that converging work — the acts of solidarity, of standing together and learning from each other as we support each other’s struggles and grow in our collective capacity for change.

PL: Why would it be important for young socialists in America today to participate in an actual mass movement?

MBM: To win the world we are fighting for, we are going to need millions more people on our side, and that doesn’t happen by talking to the same circle of people every day. Mass movements force you to speak to people who don’t look, sound, or act like your normal group of comrades. You don’t know what will come out of a conversation, despite whatever preconceived notions you have, and there’s a bit of risk in that. But if you don’t do it, then you’ll never know.

I stressed the necessity of solidarity in a mass movement, and because it’s a mass movement, that means you’re going to have to forge solidarity with people you don’t know. Outside of this context, maybe you would never speak to them. You certainly would think twice before taking a beating from the police for them. But in a moment of genuine, unadulterated struggle, you step up. We need more of that.

PL: Red squares made of felt could be recognized pinned to the bodies of protesters and their supporters all across Québec during the protests as a symbol of the student movement. I think that’s a really beautiful thing. What is the importance of having some sort of symbol to identify with? Something that makes someone acknowledge that they are now a part of this broader collective.

MBM: I think you just said it. On the one hand the person who’s giving it to you recognizes you. It says you are part of this struggle. I see you, and you matter. You are important. I am actually going out of my way to give you something. It’s a very moving thing, especially when you’re new. And on the other hand, there’s the courageous act of accepting that recognition. In certain situations, you might not accept a metaphorical red square because you don’t feel ready. You’re not ready because you can’t tell your parents, friends, or coworkers that you are with “those radicals.” And so it’s not just the action of someone recognizing you, but also you accepting it — that I am a part of this community. I will wear it. It’s empowering. It’s humanizing.

I really wish I had kept that square because I think that was the moment my life changed. I really felt like I was part of something so big for the first time in my life.