We are republishing an article by Mike Parker on the 1960s and the lessons to be learned. The following introduction is by Jeremy Gong.

Are we doomed? Left-wing activists that came to political maturity during and after the disappointing Obama years have a lot to celebrate. We also have a lot to fear, from climate change to war to a rising far right.

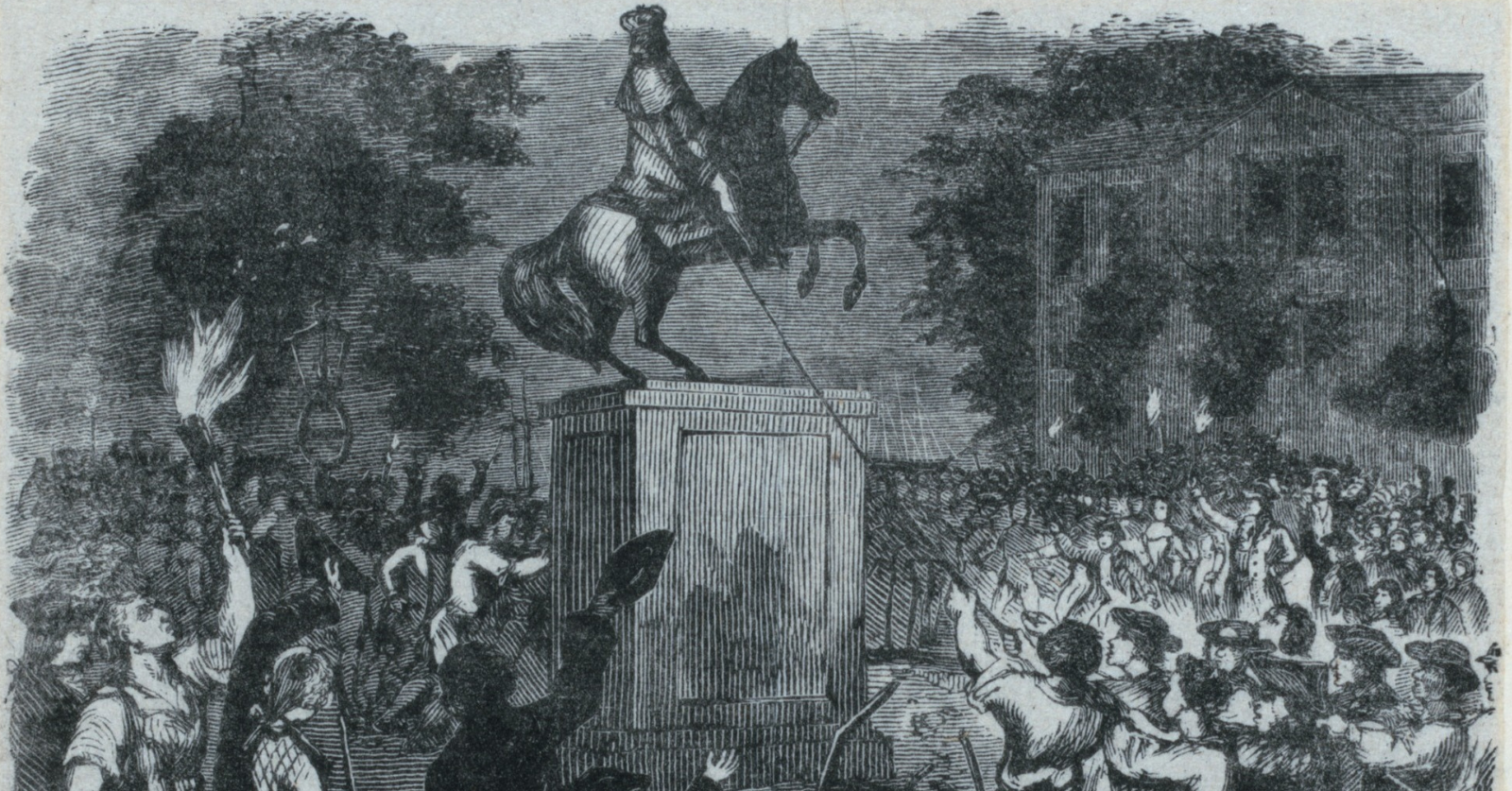

But times have been much worse. In the early 1930s, Americans faced a crippling depression, the global rise of fascism, an impending world war, and countless defeats for labor and the left. It was hard to imagine then, but in only a few years many would participate in a massive wave of resistance to the broken capitalist status quo. Millions participated in strikes, joined unions, and identified with the socialist cause.

The 1960s saw the second great upsurge of the last century. Today we take it for granted that the ’60s were radical. But in 1960, the McCarthyist Red Scare continued to ruin lives and silence dissent. Cold War militarism and the threat of nuclear apocalypse conditioned any politics allowed into the mainstream.

What changed? On February 1, 1960, 64 years ago this month, four seventeen year-old black students sat down at an all-white lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina and refused to get up. Over the next few years, millions joined their cause. The Civil Rights Movement soon grew powerful enough to force the president and Congress to act, passing anti-segregation and voting rights legislation that effectively ended the legal system of racist Southern segregation, Jim Crow.

At the same time, President John F. Kennedy, his successor Lyndon B. Johnson, and the Cold War military-industrial complex were ramping up a horrific and unjustifiable war in Vietnam. But by 1967, a massive antiwar movement, mobilizing millions in the streets, began to make the war politically unfeasible for President Johnson.

A general strike in Paris during May of that year electrified the left everywhere and national independence movements were gaining steam across the Third World. In the Midwest, thousands of black autoworkers, led by the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, began a rank-and-file revolt against the companies and a conservative United Auto Workers (UAW). For the first time since the 1930s upsurge, it became reasonable to talk about the coming revolution.

Below we are republishing an article called “Learning From the ’60s” by Mike Parker. The article is based on Mike’s remarks to a meeting of the New Socialist Group in Toronto and Guelph in 1997. Mike is best known for his contributions to Labor Notes, his book on union reform, Democracy is Power (coauthored with Martha Gruelle), and his writing on the development in the auto industry — where he worked from 1975 to 2008 — known as “lean production.” After retiring from auto, he became a leading organizer of a progressive electoral coalition in California, the Richmond Progressive Alliance, and a member of DSA and the Bread & Roses caucus. He passed away in January 2022.

Born in 1940, Mike was old enough to see the beginning of the transformative 1960s. At 19 he was already leading a national anti-nuclear weapons organization called Student Peace Union. He was active in civil rights activism as a student at the University of Chicago. In 1964 he moved to Berkeley, California and became a leader in the Free Speech Movement. He took part in a militant antiwar movement and then became the lead organizer for the Peace and Freedom Party (PFP), working closely with the then-booming Black Panther Party to run Eldridge Cleaver for president and Huey P. Newton for Congress in 1968.

Mike had considered himself a revolutionary socialist since joining the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL) at Chicago. Along with other socialist cadres, or what he refers to below as “politicals,” Mike threw himself into burgeoning movements for peace and justice in the 1960s. The rich experience of that decade shaped their ideas and strategies for the next fifty years. They became talented mass organizers, and developed sophisticated theories of how mass movements develop, transform, win, and lose. Hal Draper, the intellectual leader of Mike’s ’60s circle, described their philosophy as “socialism from below.” It’s not a coincidence that Bernie Sanders, radicalized in the same University of Chicago chapter of YPSL in the early 1960s, came out of those years with a commitment to a political revolution characterized by the slogan “Not me. Us.”

In unpublished notes for his 1997 talk, Mike wrote out a succinct explanation of how socialist cadres relate to the transformation of consciousness through struggle:

“Movements throw up new leaders. Real movements are an integration of participants’ experiences which they are forced to respond to. This makes them open to sets of ideas by political people who make it a point to learn from more abstract and detailed history. It is the people in struggle who choose. And their basis for choosing is based both on the ideas: Do they fit? And on the people: Are they part of the struggle?”

The ’60s generation didn’t “win the big cigar,” as Mike writes. But their hard won wisdom in the great struggles of that decade can serve activists in the struggles to come. — Jeremy Gong

Learning From the ’60s (1997)

We were on the eve of revolution in the ’60s, we were certain. Instead capitalism demonstrated that it was far stronger and more flexible than we understood. But we learned a lot.

Here I want to highlight five lessons I learned from the ’60s.

Lesson 1: People learn for themselves.

I used the phrase “lessons I learned” rather than simply “lessons of the ’60s” because I don’t think you can learn them from the 60’s. You may be able to learn them from your own experience. There is a lot that you can get from studying history, politics, and other cultures: some clues about your own world, and some ideas to test. But unless you actually test ideas, unless you feel for yourself how they work, unless you build them into your own mental framework, you will never really internalize them, much less let them guide you for the rest of your life. So I offer you the rest of these “lessons” from my US experience not as some kind of proven truth handed down from on high. They are ideas that became part of my political psyche and you may want to test them for yourselves under current circumstances.

Lesson 2: Massive and rapid change in political consciousness is a reasonable expectation.

When we look around now [in 1997] it is hard to imagine masses of people engaging in selfless struggle, demanding collective solutions based on values which puts the human experience first and personal economic wealth way down the list. The idea of socialism seems thoroughly discredited, corporate values and the market dominate, and “the one who has the most toys” and me-first values seem to be the motor forces of human nature.

I became politically conscious in a period which was far worse. In the 1950s, McCarthyism was the tip of the iceberg. Capitalism provided for all (except the poor who were conveniently invisible in the culture). Everyone who was willing to work could send their kids to college and have a suburban home with two cars in the garage. The American Dream seemed to work. (Black people were conveniently segregated out of view.) Socialism was either discredited and irrelevant, as Daniel Bell wrote in The End of Ideology, or it was the enemy. With very few exceptions, socialists and communists were rooted out of unions, driven underground, or “converted.” The Red Scare severed the militant leadership and the traditions they represented from the labor movement.

Politics were deeply privatized, and people would break off long-time social associations to avoid social isolation or being fired. Lawyers would not represent people accused of Communist affiliation for fear of losing their practice and even possible disbarment. The most radical public activities I heard about were those of the Green Feather Societies. Their main task was to prevent book burning in the libraries and save such books as Robin Hood. As you will recall he stole from the rich and gave to the poor — thus indoctrinating kids into socialism. In 1960 we were thrilled to participate in a polite march of hundreds, mostly Quakers and other religious groups, asking for an end to the nuclear arms race.

Yet less than a decade later, tens of thousands, particularly among blacks, considered themselves revolutionaries. Revolution was so popular that it was at the same time denounced by the Beatles in song while the lingo was coopted by corporate America. Hundreds of thousands participated in militant civil rights and antiwar struggles that ignored the laws and challenged the ability of the social apparatus to function. In 1964 Lyndon Johnson claimed the largest US presidential election landslide victory in history. By 1967 he required riot police and troops anywhere he appeared and was forced out of the race for reelection. We didn’t yet have the power to remake society. But we did have the power to stop the United States from nuclear escalation of a losing war.

As part of the struggle, the rapid change of consciousness seemed natural. We felt ourselves being transformed and it was fully reasonable that others were being transformed in similar ways in different movements.

Key events for the black movement were the sell-out at the 1964 Democratic Party convention and the ghetto uprisings in 1965 and 1966. As this movement grew it became more powerful but at the same time ran up against obstacles built into the system. The system could allow legal equality but winning decent lives was another matter. This recognition created a generation of black revolutionaries.

The famous 1964 Berkeley Free Speech Movement (FSM) began over a university ruling that a tiny strip of sidewalk near a major intersection was not public property. Thus with an edict, the university turned the campus activists, who had long used the strip for literature tables, from rule-abiding citizens to rule-breakers. The same pattern repeated itself throughout the three-month development of the movement from a back-water issue to one that engulfed the entire campus. The university, responding to pressures from the socially powerful, would commit acts revealing its disregard for the claimed values of a democratic institution. The movement, for the most part, was able to use these cracks in the facade to build its own case and strength.

The FSM developed activists who were transformed both by the exhilarating sense of collective power and a new understanding of the world as the struggle laid bare the realities of corporate control of the university.

Lesson 3: Multiple movements provide both strength and weakness.

There was rapid motion in several different sectors of American society and throughout the world. The massive stirrings in the radicalization of the Civil Rights Movement, the urban ghetto rebellions, the rise of the Black Panther Party, the antiwar struggles, and the transformation of women’s consciousness had perhaps the greatest general impact. Concurrently other ethnic groups, disabled, gay and lesbian people deepened their identity and organization. They drew from each other, learned from each other, sometimes artificially copying from each other because they all existed in the same oppressive society. But each movement experienced that oppression differently and therefore had its own character, needs, methods, and even language.

Our central task then, as today, was to find the way to converge to a common struggle while allowing each to build on its own character and agenda. It also required making difficult political choices based on some understanding of history. For example, it was easy to build struggles and get massive participation around hippie, drug culture, and flower-child issues. There were also stirrings among veterans and among factory workers, but the work was much harder and the response much slower.

The failure to build a solid base in the social power of the working class and link the other movements led to two routes of destruction. One was a vicious cycle of isolation prompting still more isolating actions. The other route accepted the boundaries of the system rather than changing it and led directly to the graveyard of social movements — the reform of the Democratic Party.

Lesson 4: Political leadership and socialist political organization were a central and necessary part of the mass struggles.

Take the Free Speech Movement. It should shock no one that much of the media and corporate establishment pictured it as a conspiracy where “Marxists-Maoists” manipulated thousands of naive students. In a futile attempt to shield the movement from the red-baiting attacks, liberals and the left itself tried to downplay the role of the organized left and portray it simply as students seeking to restore the American principles embodied in the US Bill of Rights.

In fact left organizations played a central role in the FSM. Left activists made up the core of the civil rights organizations whose activity had triggered the reaction from the university which started and maintained the FSM struggle. The FSM itself was a council of campus organizations expanded to include a few representatives of the “independents.” Goldwater and young Republican organizations were encouraged to participate, mostly as a way to deflect attack since not much was expected of them. At the same time, independents (most of whom were around one or another left organization) were actively supported for leadership.

We understood that the struggle, while initiated by the left, had to quickly broaden and become the property of a much wider part of the student body. Many new leaders emerged as the struggle intensified, and their consciousness and insight combined with the experience and training of activists from ideological left groups to successfully lead a mass movement against a very sophisticated liberal campus administration.

For the most part the experienced left leaders didn’t seek publicity. But they made contributions that were critical during the early days and at crisis points. They provided experience, training, stability, and patience. They were in organizations which backed them up, thus bringing important ready resources for the movement. They also had big picture goals that included helping new leaders emerge rather than self-promotion.

The left also helped define the broad ideological lines of the battle. When the FSM began, Hal Draper, an adult leader of the Independent Socialist Clubs (ISC) with a long history in the American socialist movement, recognized early that this was not some superficial confrontation over rules. It represented the fundamental contradiction of corporate domination of the society and therefore the campus, versus the movements of students to aid the oppressed in society.

He wrote a pamphlet describing the ideology of the university president as a spokesperson for corporate domination (in a liberal way to be sure) and the role of the university as the servant to the corporate masters. The Mind of Clark Kerr, a very sophisticated political work, had mass sales on the campus and became the “bible” of the FSM. In addition the ISC sponsored well attended public meetings, forums, and debates, taking on the ideas (and often directly the spokespeople) of the liberal opposition to the struggle helping to create political direction and climate for a large layer of new activists on campus.

Lesson 5: Struggle is valuable for its own sake.

We didn’t succeed, but we were not as far off as may appear. Had world events been different and capitalism been not quite as flexible, we might now be celebrating the ’60s as the training period for the revolutionary victors of the ’70s. But we didn’t win the big cigar, and the following decades found us trying to swim against a rapidly moving rightward stream.

Many, particularly those from the student movement at elite universities, have moved on to privileged positions in the establishment. Many of these have made their peace with their current existence and chalk off the ’60s as a rite of youth — idealistic but unrealistic.

But many have continued the struggle in almost as many different forms. We still plan to win or contribute to our progeny winning — it will just take longer. But we learned that you don’t need a guaranteed outcome or even good bet. The camaraderie in struggle combined with the liberating taste of a bit of democratic power is a unique experience. Part can be experienced in sports but without the sense of purpose. The power can be felt in business but usually requires checking your values at the door and watching your back at the same time.