Howard Zinn tells of a time when “important people in the English colonies made a discovery that would prove enormously useful for the next two hundred years.” In the late eighteenth century, American colonial elites discovered that “by creating a nation, a symbol, a legal unity called the United States, they could take over land, profits, and political power from favorites of the British Empire.” “In the process,” Zinn asserts, “they could hold back a number of potential rebellions and create a consensus of popular support for the rule of a new, privileged leadership.”

Zinn’s account of the American Revolution (from A People’s History of the United States) is a top-down affair, driven primarily by the interests of the colonial elites we call the “Founding Fathers.” It’s a common account. In fact, it’s echoed by a left-wing icon as colossal as Noam Chomsky – who asserts that one of the primary motives for the Revolution was to defend slavery.

Zinn and Chomsky’s story of American independence is similar to what Herbert Aptheker observed was “the dominant trend in recent American historiography” in his time. This trend saw the American Revolution as “quite unique” in history, in that “it was either no ‘revolution’ at all, or, if a ‘revolution,’ then a conservative one.”

In his forgotten classic from 1960, The American Revolution 1763-1783, Aptheker decisively rejected this trend. Rather, he placed it in the “general pattern of the ‘New Conservatism’” that dominated much of that period of historiography. Aptheker — a titan of the Old Left and house historian of the CPUSA —instead viewed the “struggle against British domination” as “a continuation of the pro-democratic struggles that had formed so central a part of colonial history as a whole.” The Revolution was a popular uprising for democracy that, while constrained by elite interests, was not dominated by them.

Origins of Revolution

If, as Zinn and Chomsky imply, the American Revolution was exclusively the project of colonial elites like George Washington or John Adams, we would expect this to determine the factors and grievances that led up to the revolt. To Zinn and Chomsky’s credit, there is some evidence for this. For example, Apethker writes about how southern planters were in “economic bondage” to the British merchant class. Many of these planters, including Thomas Jefferson, had been in debt to British creditors for generations — to the point that Apethker described them as “a species of property, annexed to certain mercantile houses in London.”

Yet it is also true that “British power” had long served as “the last resort of home-grown and British-fed reaction” in the colonies. Aptheker points out that during the Revolution the largest slave-owners typically sided with the crown, because they had relied on British strength to repress revolts by slaves and small-holding farmers for generations. This was just the case for the rebellion of the Regulators in the late 1760s, who were crushed by the royal governor William Tryon. While Tryon went on to be a major commander of in the loyalist militia during the Revolutionary War, Aptheker cites that of the 323 known Regulators who participated in the war, almost ninety percent of them fought with the Patriots.

It’s also doubtful that the British had any intention of ending slavery in the near future if the colonies were defeated. Aptheker points out that those slaves “freed” by British forces during the war typically “found harsh treatment, disease, sale to slavery in the West Indies, or death.” The British Empire did not abolish slavery until 1832, 56 years after American Independence, and even then, slavery wasn’t abolished so much as outsourced. The Empire was still reliant on American slave-grown cotton, and provided instrumental military support to the Confederacy during the Civil War. British involvement was likely the only reason the war lasted longer than 12 to 18 months.

While independence was popular among less prosperous slaveholders, who were eager to get out from under the thumb of British merchants, independence still had broader appeal. As Aptheker cites, British revenue from American customs fees alone increased fifteen times over during the course of the 1760s, despite the fact that trans-Atlantic trade was in complete collapse — British exports to New York City at this time fell by nearly eighty-five percent in the course of two years, in no small part due to organized colonial resistance to British taxation.

The result was that “there was no area of American colonial life that went unaffected by the British policies and interests.” The colonies were utterly reliant on England for manufactured goods. Imperial law banned the production of industrial goods like steel in the colonies, and the colonists were not permitted to import goods from competing foreign powers. Further, the colonies were already in what Aptheker describes as “severe economic depression” while these taxes were being rolled out in the wake of the French & Indian War. Hundreds of thousands of colonists felt the squeeze between rising tax burden, economic downturn, and skyrocketing prices of consumer goods — enough to form the material basis for a revolutionary coalition.

Mass Movement

Not only did the Patriots have the muscle of popular power on their side, but Aptheker also affirms that they would likely have lost without it. He dismisses the almost ubiquitous misreading of John Adams, repeated ad nauseam by lazy historians, that only a third of Americans supported the Patriot cause. Instead, he insists that “the actual success of [the] Revolution … despite great hardships, enormous handicaps and a very powerful and persistent foe, is the best evidence that the majority” sought to carry “the effort to a successful conclusion.”

Aptheker backs this with the electoral data we have from the time. Suffrage was far from universal in colonial America, but it was wider than anywhere else in the world during that period. As much as seventy percent of adult men could vote in some areas, including free black men in the North, compared to the one in thirty adult men granted the vote in England. Thus, the sweeping electoral victories of the Patriots throughout the 1760s and ‘70s were indicative of widespread popular support.

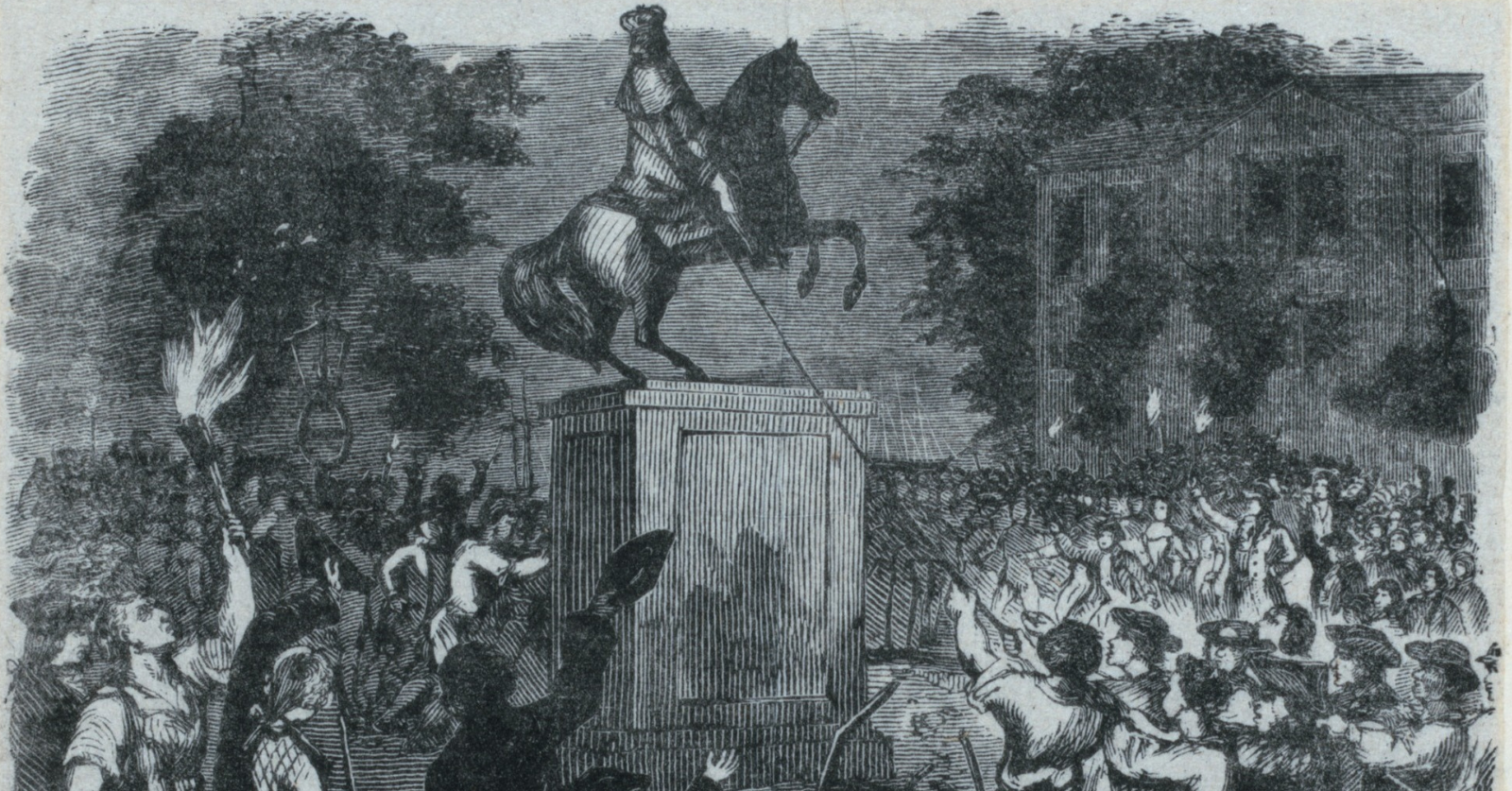

The mass character of the Revolution was also characterized by the revolutionary organizations formed by Patriots. Illegal town meetings and provincial assemblies garnered mass grassroots participation. Committees of Correspondence and of Safety facilitated discipline and coordination of collective action across vast distances, such as boycotts of British goods and non-importation agreements. Rudimentary trade unions organized political strikes, as when Boston construction workers struck in 1768, refusing to build fortifications for the British Army. The Sons of Liberty were the most prominent: founded during struggles against British taxation in the 1760s as a secret society, they gave up secrecy once “they became numerous enough to make legal persecution unwise and unlikely.”

Domestic opposition in Britain was a factor too. Aptheker contends that one “cannot understand the American victory and the defeat of the king’s policy” without understanding the “strong opposition to the policy of George III that existed inside England” itself. In fact, Granville Sharp, a prominent English abolitionist and one of the leading figures in the court case that Chomsky cites as the reason Americans sought to defend slavery, was one of numerous British officials and military officers who resigned their positions in protest against the crown’s war against the colonies. American Patriots were in constant contact with the English Whigs, the anti-war opposition throughout the years leading up to and during the war for independence. Both English and international popular support played a key (though largely forgotten role) in the Patriots’ victory.

Class Divisions

The Revolution was not imposed by elites onto an indifferent populace. An important example of this was Gouverneur Morris, who later authored the preamble of the US Constitution, and who “decided to cast his lot not with the king, but with his country and to attempt, at the same time, to minimize the revolutionary changes.”

Morris had “no hope that our union can subsist except in the form of an absolute monarchy,” and would later conspire with Alexander Hamilton and the Society of Cincinnati — a shadowy organization of pissed-off Revolutionary War officers — to overthrow the Continental Congress and install a military government under George Washington. Washington himself opposed this, though it was a popular idea among officers and creditors who did not believe that Congress could, or would, pay off its debts to them.

Despite being quite popular among the wealthy elite in the young republic, Hamilton’s plot was foiled. This is in part due to Washington’s refusal to play the part of an American Caesar, but even more so because Hamilton and Morris realized that a military dictatorship would never survive the country’s popular backlash. Though Morris himself desired a return to monarchy, he realized that “this does not seem to consist with the taste and temper of the people.” Hamilton blatantly admitted that “could force avail, I should almost wish to see it employed,” though he realized that such an effort would be futile. In this telling, Aptheker makes it clear that many American elites would have happily installed a much more reactionary government in the independent colonies, had they only been able to. Woody Holton’s essential study of post-Revolutionary America, Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution, is an excellent further reading on this topic.

A Popular Retelling

Aptheker’s American Revolution is an extremely valuable contribution to the Left’s literature on the period and deserves far more recognition than it receives today. Chomsky and Zinn make a valuable contribution to a Left-wing interpretation of American history by highlighting the undemocratic and extremely reactionary tendencies among American elites going back to this nation’s founding. But in doing so, they have a tendency to erase or ignore the agency and power of popular classes that made essentially progressive events like the American Revolution possible.

The book has its flaws. Aptheker paints judicial independence and the separation of powers as a victory for democracy, for example, in that these rules “may [emphasis is original] serve to protect the rights of dissident and radical minorities.” Perhaps that interpretation made more sense in 1960 in the wake of Brown v. Board of Ed, but it certainly seems anachronistic today.

Nevertheless, Aptheker’s account is one of exceedingly few Marxist tellings of the Revolution in the modern era, and for that reason, deserves special attention. He concludes that, for all its flaws, the “promulgation of popular sovereignty” achieved by the Revolution “as the only legitimate basis for governmental power was a basically revolutionary event and one fundamental to a democratic society.” Thus, the revolutionary ideology “represented a fundamental break with feudal and monarchical thinking and in this respect had the widest international ramifications.” That progress, if nothing else, is worth celebrating.