Brazil’s Socialism and Liberty Party (Partido Socialismo e Liberdade, PSOL) was formed in 2004 after some of its founding members were expelled from the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT) in 2003 for opposing pension cutbacks proposed by the government of President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. These reforms were also opposed by public-sector workers. Today, PSOL is a significant political force in Brazil, with more than 290,000 party members, a strong youth wing, and activists embedded in social movements and labor unions. PSOL also has 13 deputies in the lower house of the country’s National Congress and many more elected politicians at the state and local level. While smaller than the center-left Workers’ Party, in the 2022 General Election its candidates for the Chamber of Deputies received a total of 3.9 million votes to the PT’s 13.2 million.

For democratic socialists in the U.S. looking to build a new party of the left, PSOL is an important reference point (as is the PT). DSA has around 70,000 members, a handful of elected officials in Congress (though they mostly do not coordinate with DSA), and scores of elected officials at the state and local level. Like PSOL, DSA is a multi-tendency organization working to implant itself in the labor, social, and student movements. And like PSOL, DSA is dealing with the challenge of fighting a powerful far right and simultaneously contesting for the loyalty of working-class and popular forces with a much larger center-left party. Not to mention that both PSOL and DSA are organizing in continent-size countries with massive populations and deep histories of racism and settler colonialism. There are significant differences of course — by far the most important being DSA’s task of fighting U.S. imperialism from within “the belly of the beast.” But as DSA gets more serious about party building and organizing, learning from comrades carrying out similar work in other countries becomes more and more necessary. This interview with comrades from Brazil is the first in what we hope will be a series of discussions with comrades from parties and movements around the world.

For this interview, The Call’s editor Neal Meyer talked with Pedro Fuentes and Mariana Riscali to get their perspectives on the world political situation, organizing in Brazil, and the strategic debates inside PSOL. Pedro is a founding member of PSOL, the party’s first international secretary, and a leader of the Left Socialist Movement (Movimento Esquerda Socialista, MES), a political tendency inside the party. Mariana is a member of the MES leadership committee and the treasurer of PSOL.

The Interview

1. We’re talking at a moment of great uncertainty for the international working class and the left and other progressive forces. We’re seeing the return of inter-imperial rivalries, as the U.S. and Europe face off against Russia and China. Signs of a new financial crisis are building. The climate crisis grows more acute. The far right’s attacks on the rights of racial minorities, women, queer people, and Indigenous people are growing more intense and are becoming more coordinated across the globe. What is your perspective on the international political situation? How should socialists respond to the return of inter-imperial hostilities?

Pedro Fuentes: Your question contains several aspects, all very important. We agree that we are living in a period of uncertainty about the world situation. What is it that causes so many uncertainties? There is a series of interrelated crises of the capitalist system: the economic crisis, climatic crisis (both with tremendous repercussions for the lives of workers and especially those in the Global South living under imperialism), a deep social crisis, and also a crisis in the world order. The war in Ukraine as a result of the Russian invasion occurs in the context of the sharpening of the inter-imperialist competition that you mention. The crisis of the bourgeois democratic regimes and the rise of xenophobic authoritarianism, which among other things also denies the climate crisis and individual liberties, is part of a situation of world disorder. It is a multidimensional crisis that shows the state of agony of capitalism. As the English economist Michael Roberts says, capitalism has already passed its use-by date.

The contradiction is that the alternative to this system, which is international socialism, lags far behind in relation to the crisis we are facing because socialist consciousness has been setback as a consequence of the failed experiences of “actually-existing socialism” that existed for a third of humanity (Russia, the countries of Eastern Europe, China…). It was a misnamed socialism, because two fundamental elements of socialism were missing: first, democracy within those states (that is, the necessary freedoms to advance socialism within the country and in the world), and second, the struggle to spread the revolution and thereby advance against capitalism on a world scale.

What is the perspective of the world situation? Capitalism does not die by itself; without class struggle, without revolutions, if we do not build that anti-capitalist alternative, it will lead us to barbarism. Rosa Luxemburg’s dichotomy of “socialism or barbarism” from a hundred years ago is more present than ever. Let’s think that the climate crisis sets a life date for humanity. The advance of the authoritarian right is “more coordinated,” and I would also say that they will be more aggressive and violent. It is the most dangerous enemy that we have to face because it would lead us rapidly to that barbarism.

But at the same time, there is great resistance in the world to this advance by the far right that we can say is anti-civilizing. There is another pole that stands out and it comes in the form of the mobilizations that are taking place. An example from recent days is the mobilization of Greek youth in protest against the authorities who were accused of intentionally letting a boat sink that was sailing from Libya with 700 people who emigrated at great risk to try to have a new life in Europe.

Everywhere there is a reaction, even in China itself there is resistance. Latin America is witnessing permanent mobilizations. They still do not have a consistent, anticapitalist leadership, but they resist the right and confront neoliberal plans. We are optimistic about what happened in France. Despite the fact that the pension age reform passed, there has been a mass political break with neoliberalism from which many new things may emerge. Also with the situation of the working class in the USA. It is not a process that can already be marked as the fundamental feature of American politics, but nevertheless it is a process — we could say still underground — that is going to move the tectonic plates of American imperialism. In other words, for socialists the fight is open and we are as enthusiastic as you are about the opportunities that are emerging. In the working class, in its mobilizations and that of the other oppressed sectors, we have to be present to take steps to build that anticapitalist alternative. It is a difficult task, but not impossible.

Regarding the dispute between China-Russia and the U.S.-Europe, we believe that it is wrong to think that there are good imperialisms and bad imperialisms; that is, that there is a progressive imperialist camp that we should support. China is also an imperialist state — although emerging — newer in this role than the U.S., but no less aggressive for that, mainly from the economic point of view. In the case of South America, China has come to play a more important role than the U.S. Its loans to countries are made with interest rates as high as or higher than those of the global financial market. (In the case of Venezuela, they are higher and it is charging them!) It extracts surplus value from the factories installed in the region and plays a fundamental role in the extraction of minerals and the consequent environmental contamination. Its military capacity is increasing rapidly and although it does not have the strength of the United States, as its economic influence increases, it will also grow militarily.

For these reasons, our dividing line to define the allies we have is determined not by countries but between the exploiters and the exploited and between imperialist countries and the self-determination of the peoples. That is why we are together with the Ukrainian people against the foreign invasion, with the Palestinians in their struggle for the reconquest of their territory, and with the workers and oppressed sectors of the whole world. We are committed to the resurgence of the internationalism of the workers, coming to the aid of the internationalism of all the oppressed.

2. The people of Brazil defeated the far right government of Jair Bolsonaro in October 2022. His successor, Lula from the Workers’ Party, took over in January. What is your analysis of Lula’s government so far? Have there been progressive developments? Setbacks?

Pedro Fuentes: Yes, Bolsonaro’s defeat was a very important victory. If he had won, we would be witnessing a regime change that would have liquidated all democratic freedoms. We would be on the way to a totalitarianism with fascist traits. This perspective was closed, which does not mean that “Bolsonarism” is finished; he lost power, but he retains a lot of strength since his party managed to reach parliament with a significant force and continues to retain the support of a sector of the bourgeoisie — especially in agribusiness — and he has 20% of the population who follow him, especially in the upper middle class. Something similar (not exactly the same, however) to what has happened in the U.S. with Trump.

Lula triumphed in a coalition that included important sectors of the bourgeoisie. His Vice President Geraldo Alckmin is one of the representatives of this class. And his cabinet is made up of a mix of members of the PT as well as more direct representatives of bourgeois parties, including the Brazil Union, the Brazilian Democratic Movement, the Social Democratic Party, which were even part of or supported the Bolsonaro government.

On the other hand, and this is fundamental to characterize the government, the PT has long ceased to be an independent party. It assimilated to the bourgeois regime as it began winning elections and taking over the government of cities and states, abandoning its original program. We define this government as bourgeois, because the bourgeoisie and proven agents of it like the PT are in power.

There are more independent figures in the cabinet, such as Silvio Almeida in the Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship, or the Indigenous leader and member of my party, PSOL, Sonia Guajajara in the Ministry of Indigenous People. But they are a concession to the left by the rest of the government. In history, the bourgeoisie or their agents have never ruled in a way contrary to their interests. We can say that it is a type of bourgeois government with a liberal social policy, of class conciliation, but a bourgeois government after all, with features similar to European social democratic governments.

It certainly created expectations that are still maintained to a lesser extent as a result of the concessions made by Lula in his two previous governments. At that time there was then a favorable economic situation due to the prices of raw materials on the world market, and for this reason he was able to make some concessions to the workers. However, we are now in a different situation. Brazil is part of the world crisis that we mentioned earlier and that forces governments to apply strong economic adjustment plans at the service of the big bourgeoisie.

On the other hand, we have a parliament where the government bloc is in the minority, and it is not willing to mobilize supporters — as President Gustavo Petro did in Colombia when his health plans were not approved in the legislature. Congress here has ended up creating a draft government spending plan limiting social spending with a strict ceiling that will instead prioritize the payment of public debt to bankers and financial capital in general. There have however been some advances with the payment of a family grant to needy families, and in the field of defense of the Yanomami indigenous population that was on the verge of extinction due to hunger and disease due to the policy of the previous government. But at the same time, the bourgeois majority voted in favor recently of a limit on the land occupied by the Indigenous population defined by the 1989 constitution. But now the area occupied by the Indigenous people is much larger than it was 30 years ago, and the agribusinesses want to reclaim these territories. These lands are to be cleared and handed over to agribusiness.

3. And what about the right? Earlier in June, the right-wing Liberal Party launched an attack on left-wing parliamentarians from the Workers’ Party and PSOL. What is the strategy of the right? What are their chances of returning to state power?

Pedro Fuentes: The right lost power, but it retains strength in the Chamber of Deputies (the Liberal Party which Bolsonaro is a member of has the largest number of deputies, 100 out of 504), as a social force with 15 to 20% of the population as firm supporters, and also as a serious power in the armed forces and police (where it is especially strong in the intermediate command levels). The right also retains its influence on social media. In the Chamber of Deputies, the evangelical bench and the agribusiness bench make up an important part of the ultra-right.

Six deputies, Célia Xakriabá (PSOL), Sâmia Bomfim (PSOL), Talíria Petrone (PSOL), Fernanda Melchionna (PSOL), Juliana Cardoso (PT), and Erika Kokay (PT), have been sent to the Ethics Committee of the Chamber, a procedure that could end with the annulment of their right to hold office. A campaign is being carried out to defend the compañeras from this attack that is misogynistic as well as politically motivated.

Another hard attack from the right is against the MST (Landless Workers’ Movement), which was accused of violating private property and practicing terrorism. They have set up a Parliamentary Investigation Commission in which our deputy Samia Bonfim is a leader of the defense of the MST. These are ongoing processes for which a broad campaign of solidarity with the deputies and the MST must be carried out.

The future perspective of Bolsonarismo will depend on two issues. One of them depends on how Lula continues to rule. If there is great disappointment, it is clear that the extreme right, whether with Bolosonaro or another leader at its head, will grow.

The other depends on the possible disqualification of Bolsonaro, who, like Trump, faces many legal cases. Unlike in the U.S., a conviction disqualifies him from running for election for eight years. If this happens, however, the right has figures who can replace him.

Next year’s municipal elections will be an indication of what electoral strength the right continues to have. Beyond these immediate prospects, we believe that PSOL will continue to grow as long as it maintains a firm policy against the right and — at the same time — independent of the government.

4. What of the left? What is PSOL’s strategy in this moment? What are the debates inside PSOL about how to respond to Lula’s government and to fight the right? Are you primarily on the defensive, or are there opportunities to go on the offensive?

Pedro Fuentes: PSOL is a party with 20 years of existence. Today we can affirm that it is the most important left-wing party in Brazil in the face of the strategic bankruptcy of the PT and the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB), a party that comes from Maoism and that today is in an alliance with the PT. Both parties are part of the power structure and are in the government. Against those who did not believe that it was possible to build a party to the left of the PT, we have built a party with almost 300,000 members, including thousands of militants [organizers and activists] embedded in the worker, popular, peasant, and student movements. The parliamentary representation for PSOL that was won demonstrated that it was possible to build a party of the left to occupy the space vacated by the PT’s decision to assume the management of the bourgeois state and to follow a strategy for the development of national capitalism. This was the minimal founding project of the PSOL with its strategy of running as an anticapitalist party with mass influence.

Now, the PSOL is under pressure from the bourgeois power structure and for this very reason we can affirm that it has contradictions. It is an extremely progressive project due to its symbolism, its social base, and part of its parliamentary caucus. It has important anticapitalist currents. But there are great gaps and important risks, such as dilution into the PT, the lack of a strategic project, and an undefined relationship with the state.

Today, this is expressed in a considerable sector of the party leadership that acts as if it were part of the government; we refer to a whole sector that revolves around Guilherme Boulos [a Federal Deputy and activist in PSOL] as well as the president of the party. On the other hand, there is another sector in which there are those who founded PSOL, who defend and have a policy independent of the government. We refer to our tendency MES and other currents that form a left bloc. Nothing is decided yet. PSOL is a living party under pressure from real movements. Thus it was that it refused to vote for the candidate for president of the Chamber of Deputies chosen by the Lula government, instead presenting its own candidate, and voted against the budget project that set a limit on expenses and that mainly hit health and education.

MES as an internal current of the PSOL is growing. Our policy has two central tasks that are combined. On the one hand we must confront the ultra-right and fight to send Bolsonaro and his partners to prison. We must confront the policy of attacking the demands of women and the xenophobic policies that this extreme right defends and tries to implement in the Chamber of Deputies. We must oppose the attempts of agribusiness to invade Indigenous lands. At the same time we are independent of the government. We will defend it from attacks from the right, but our job is to fight for the interests of workers and poor people.

5. In the U.S., there is a great deal of excitement about the return of a more militant, left-wing, and democratic labor movement here. I wonder how socialists in your party, PSOL, are involved in the Brazilian labor movement? Are the ties between the left and labor strong? Are most of the unions still loyal to the PT? Is there a sense that unions are prepared to open up a new drive to organize new workers, or are they on the defensive?

Pedro Fuentes: The PSOL as a whole has its largest participation in parliament, but its union participation has been growing, especially thanks to the more left-wing currents and a tradition of organizing among workers in groups including MES. Today PSOL as a whole and MES as well are strong in the sector of public service workers. At the federal level, we have leadership in a majority of unions of university employees, university professors, and we run several unions of basic education teachers. We are still weak in the industrial worker sectors. The exceptions are the chemical workers, the oil workers where we have some insertion as PSOL, and recently a section of metallurgical workers.

What are the ties between the left and the workers? Most of the union leaders are affiliated with center-left parties and the PT. It has a majority in the unions with bureaucratic leaderships. The membership base is looser, for now apathetic. The exception are those categories that I mention in the hands of more grassroots parties such as the PSOL. The PT maintains its strength among the industrial workers, who for now are the ones that have mobilized the least. Among public workers it is different because they have already had some experience with the PT governments.

We can say that the labor movement is still on the defensive. At the same time, strikes are growing among teachers and subway workers, and in the oil tankers there have been important strikes. This summer a strike is taking place in the union of education workers in Rio de Janeiro where the PSOL and especially the MES have the majority in the leadership. The strike has local or sectional strike committees and weekly general assemblies are held to decide what to do. The delivery workers are also organized and are taking important actions to demand their rights.

On the other hand, there are the struggles in the countryside that continue to set the current agrarian reform agenda. The “landless” movements suffer a strong attack from agribusiness, the majority of which continues to support Bolsonaro. The PSOL — and especially the MES — have strengthened our work in the countryside and have militants in the MST, FNL, MLST, Movimento Nossa Terra, and Movimento Popular de Luta, all of which are organizing land occupations.

We also have to take into account the conflicts that exist in the Amazon jungle, which is a strategic territory and hotly disputed, in which the peoples of the region are under a deadly siege, at the behest of landowners, land grabbers, loggers, and prospectors, with the support of rural and urban political and economic elites. PSOL has gained a presence in this area, which is strategic and where Indigenous people, the Black communities called quilombolas, riverside residents, small farmers and other rural workers who continue in the resistance have built processes of reconquest of their territories. At the same time, they build forms of life and processes of sociability that resist capital’s notion of time and space, affirming values, cultures, and knowledge that oppose the logic of the market.

6. This summer is the ten-year anniversary of the 2013 popular uprisings in Brazil against neoliberalism — the “June Days.” What is the state of Brazilian popular and social movements now, ten years later? What movements play a leading role in fighting for social rights and in radicalizing young people?

Mariana Riscali: This is a very important question because a large part of the Brazilian media, social movements, and left-wing parties, including the PT, seem to have forgotten the “June Days.”

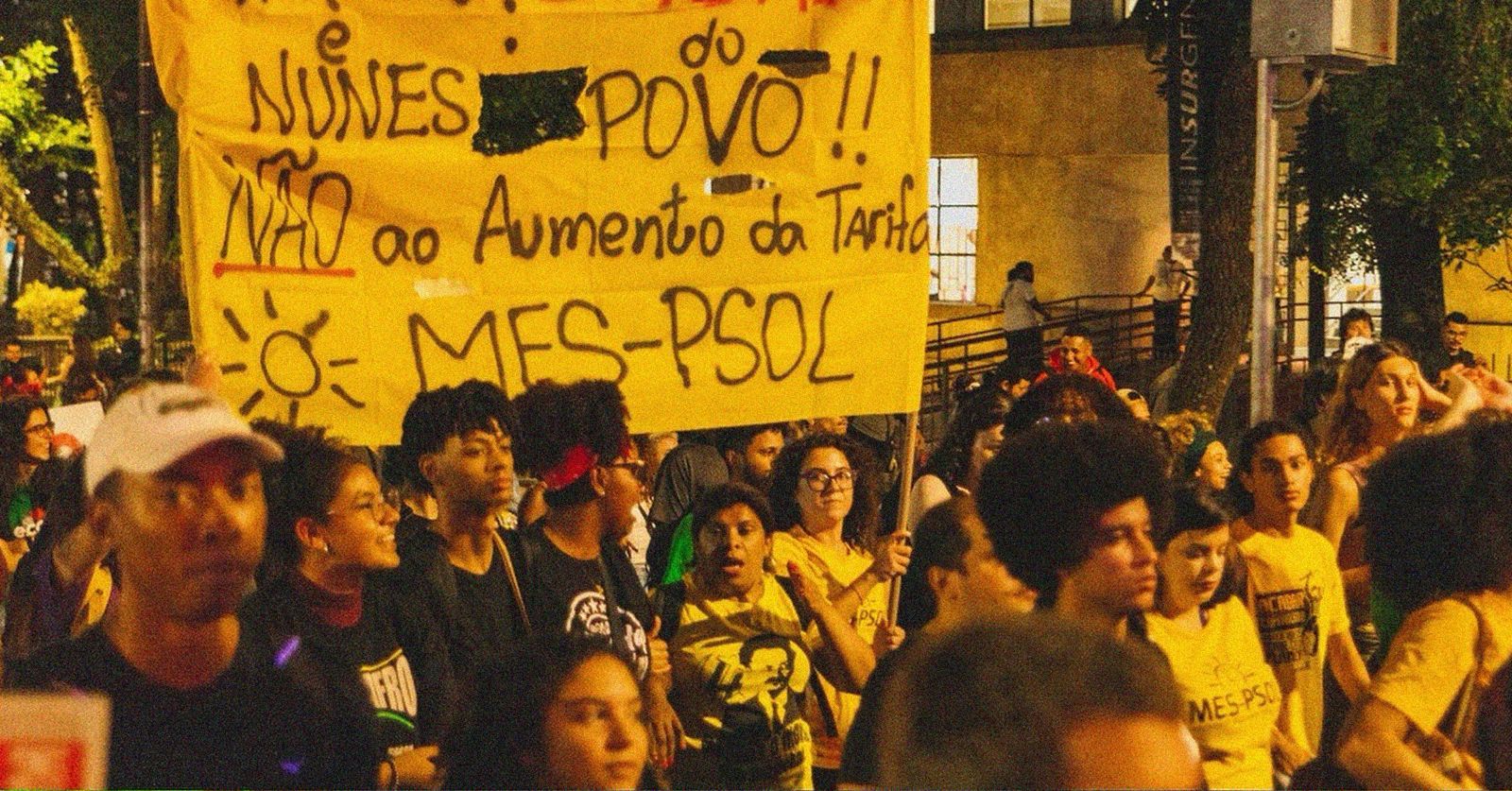

That happens among the elite because it is obviously not in their interest to remind people that mass protests are a path to social conquests — there were important victories in 2013, such as the reduction of public transit fares, the main demand that motivated the start of the protests.

Among the left, we have two ways of understanding the revolts.

One way of thinking is that, from the beginning, the uprisings had an “anti-political” motivation. That it was mainly conservative people who took to the streets. This would even explain why later, in 2016, the large protests channeled by the right, which contributed to the parliamentary coup that ousted former president Dilma Rousseff, opened the way for the right and for Jair Bolsonaro.

But for us this is a complete misunderstanding or even an intentional distortion of the character of the June protests. There was enormous dissatisfaction, and not only because of transit rates but also because Brazil was also affected by the international crisis that began in 2008, and a significant part of the lower and middle classes suffered from lower incomes, huge debts, and a reduction in the investment in public services. There was a great rejection of the traditional politicians and political parties, and we cannot forget that the PT governed not only with Dilma but also with Fernando Haddad, mayor of São Paulo at the time (and today Lula’s finance minister, one of the members of the government most supported by liberal sectors).

Once we understand that, we cannot say that the protesters were right-wing oriented. What happened was that a significant part of the left, especially the PT that was in government, did not know, or did not even try to understand and respond to that general economic, social, and political dissatisfaction. And that opened the way for the right to address those feelings and present itself as an alternative.

As revolutionary socialists we have to support and encourage street mobilizations and defend the collective self-organization of social movements. And that is why as MES we are remembering the 10-year anniversary of the “June Days” as a way of reinforcing the importance of street mobilization and social movements. Even now that we have electorally defeated Bolsonaro, the organization of social movements and of the working class is the strongest way to achieve social change. Some movements related to the PT will try to “cool down” or stop the mobilizations to protect Lula. We will defend Lula’s government against an attack from the right, but we are sure that it is necessary to stay mobilized to fight for our rights. An example of a movement that plays a role among young people is Together! (Juntos!) a movement of youth and students organized by the MES, which played an important role in the 2013 mobilizations and continues to grow in high schools and universities across the country.

7. How is PSOL now? What is the social base of the party? What is PSOL’s policy towards the PT? How many members does the party have? How many elected officials?

Mariana Riscali: PSOL is today the second largest party of the Brazilian left, with close to 300,000 members, 13 federal deputies, 22 state deputies, and 88 councilors in 14 states of the country. PSOL has a solid base, especially in a base of civil servants, especially in education. The student movement and among young people in general is an important part of our social base. PSOL also occupies a very large space among sectors of the feminist, Black, LGBTQIA+ vanguard where, for us of the MES, it is necessary to go beyond demands for representation but also to ensure that PSOL is consistent in defending these groups where they are most affected by social inequality, that is, among the working class.

Our policy in relation to the PT is part of a broader debate on PSOL’s strategy in the face of the new Brazilian situation, with the election of Lula. There are sectors of the party that defend being part of the PT government, supporting and voting in favor of its bills, and holding positions in the executive. We of the MES, together with what is considered the “left wing” of PSOL, think that the party should be independent. We are independent of the government in the sense that we are critical of measures it takes that are anti-worker, etc. At the same time, we defend the government when it is attacked by the far right and we do not give up the unity with the PT necessary to combat the extreme right and Bolsonarismo. But we are capable of having the necessary independence to defend a left-wing program. PSOL must indicate different solutions when the government’s policies are in contradiction with the interests of the workers and the social movements. And this government policy against the interests of the workers has been happening.

8. Finally, MES is a founding member of PSOL. How strong is MES at the moment? What are your major areas of work? What is MES’s vision for PSOL?

Mariana Riscali: MES is today the largest group on the left of PSOL. We hold the national treasury of the party, and we have several state presidencies and other positions in local leaderships. We have two federal deputies, Sâmia Bomfim and Fernanda Melchiona, among other parliamentarians, who are part of MES. MES is present in 20 of the 26 states of the country, in addition to the Federal District. And our action goes further, because we are also in social movements like Juntos!, Juntas!, Emancipa, FNL, in the trade union movement especially in the areas of education and health, in the ecosocialist movement and in the rural struggle, like MST, FNL, MLST, MNT, and MPL.

We from MES founded the PSOL as a project to overcome the PT, to become an anticapitalist party with mass influence. As we have already said, your project is at risk if the weight of the pragmatic sectors leads the party to a path of greater integration with the bourgeois regime. For this reason, the 8th National Congress of the PSOL, which is taking place this year [in late September and early October] will have a decisive role in shaping the direction of the party, and we from MES are committed to mobilizing the base of the party to carry out this debate and defend a militant PSOL project.

We are also internationalists, we are members of the Fourth International, and we believe that it is essential to keep up to date with international mobilizations, to bet on the organization of the world left and its processes of struggle. We have watched with great enthusiasm from the beginning the emergence of DSA as an organization capable of renewing and influencing the American left, and we want to continue acting together in building that necessary internationalist socialist alternative that must be built globally to defeat capitalism.